Letter From the Editor

My name is Vanessa Aponte, and I’ve had the pleasure of serving as the Editor-in-Chief of UNLV’s Undergraduate Law Review for the past 2½ years. As graduation approaches, I have been reflecting on this organization and my time leading it. I remember when I first found ULR in the Involvement Center, searching for any clubs that had the word “law” in it. Amidst a pandemic and a severe bout of imposter syndrome, the newly-founded Undergraduate Law Review spoke to me. I applied for a leadership position and, even after underestimating my ability, I was given the opportunity to serve as an inaugural Associate Editor. After months of editing articles and helping writers through the process, my dedication was rewarded with the position of Editor-in-Chief. The rest is history.

June 2023 | Vanessa Aponte (Former Editor-in-Chief)

Dear Esteemed Reader,

My name is Vanessa Aponte, and I’ve had the pleasure of serving as the Editor-in-Chief of UNLV’s Undergraduate Law Review for the past 2½ years. As graduation approaches, I have been reflecting on this organization and my time leading it. I remember when I first found ULR in the Involvement Center, searching for any clubs that had the word “law” in it. Amidst a pandemic and a severe bout of imposter syndrome, the newly-founded Undergraduate Law Review spoke to me. I applied for a leadership position and, even after underestimating my ability, I was given the opportunity to serve as an inaugural Associate Editor. After months of editing articles and helping writers through the process, my dedication was rewarded with the position of Editor-in-Chief. The rest is history.

During my tenure, ULR has successfully published over 30 articles, educating the public on everything from defamation to tax law to labor rights to intellectual property. We’ve covered countless Supreme Court cases and pieces of legislation, carefully analyzing the constitutional legitimacy of every topic. Some of the articles have focused solely on local Nevada laws, while others have discussed laws in various other states. We’ve even had the pleasure of receiving submissions from undergraduate students in Illinois. Now, after all this time, I’m so grateful that my curiosity led me to this organization. I’m even more grateful for the opportunity to oversee it and watch ULR blossom into a respectable law review.

I’d like to thank all my executive board members across these past 2½ years who have helped me run ULR. There has always been a dedicated team behind this organization, and that teamwork truly made the dream work. Any time I felt overwhelmed or made mistakes, I could always count on them to find solutions and take responsibilities off my plate. I’d also like to thank everyone who has been a part of ULR while I have served in this leadership role. The writers never ceased to amaze me with their passion, and the editors always gave wonderful feedback during meetings. This organization’s success is not mine to claim—it is the collective work of each ULR member that poured their heart and soul into every article. Thank you from the bottom of my heart for always giving it your all, and I cannot wait to see how future publications progress beyond my wildest imagination. Finally, none of this would have been possible without ULR’s founder and first Editor-in-Chief, Kyle Catarata, as well as our faculty advisor from Boyd School of Law, Joseph Regalia. You both have my infinite gratitude.

To my successor, Annie Vong: I am so proud of you. Like many ULR members, you joined the club with so much enthusiasm. I watched your writing improve tremendously, and I was overjoyed when you applied for Associate Editor and then Editor-in-Chief. You are the embodiment of success within ULR, and I have no doubt that you will lead this organization into greatness. I’m so excited to see how ULR thrives under your leadership, and please know that I’m always here to support you and the club at large (albeit as a Boyd Law student now instead of an undergrad). If you ever need anything, I’m only a short walk away!

If you’ve made it this far into the letter, please continue keeping up with our publications. Not only will you learn the law in a digestable manner, but you will also be supporting the work of undergraduate pre-law students with no other avenue to hone their legal writing skills. We write for you, so please read for us. I promise you won’t regret it.

Sincerely,

Vanessa Aponte

Associate Editor (2020-2021)

Editor-in-Chief (2021-2023)

Abortion: Troubling Legal Concerns in a Post-Roe America

In 1839, someone reading a copy of the New York Sun may have noticed an advertisement addressed to married women from a physician named “Madame Restell,” claiming to have medicine that would “alleviate private difficulties” and “remove obstructions.” After mailing Madame Restell a few dollars, a person would receive a powder or some pills that contained ingredients such as pennyroyal, black draught, ergot of rye, and motherwort. These ingredients sound like a recipe from Hocus Pocus, but Madame Restell was no witch. She was an abortion provider almost two centuries ago, infamously dubbed the “Wickedest Woman in New York” due to her services. Despite her notoriety, Madame Restell’s practice shows just how prevalent the issue of abortion has been over time. Abortion is defined as the intentional termination of a pregnancy and, as far back as 1550 BCE, humans have managed unwanted pregnancies by obtaining abortions. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reported about 620,000 abortions in 2020, or roughly 11 abortions for every 1,000 women ages 15-44. The legality of abortion in the United States used to be protected under Roe v. Wade (1973), but after the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), Americans no longer have a federally protected right to abortion under the U.S. Constitution. This new ruling upended 50 years of precedent and triggered a wave of abortion bans across the country. As abortion becomes criminalized again in many states, it is imperative to understand the history of reproductive rights in the U.S. and the troubling legal concerns that arise in a post-Roe America.

April 2023 | Vanessa Aponte [former] Editor-in-Chief

In 1839, someone reading a copy of the New York Sun may have noticed an advertisement addressed to married women from a physician named “Madame Restell,” claiming to have medicine that would “alleviate private difficulties” and “remove obstructions.” [1] After mailing Madame Restell a few dollars, a person would receive a powder or some pills that contained ingredients such as pennyroyal, black draught, ergot of rye, and motherwort. These ingredients sound like a recipe from Hocus Pocus, but Madame Restell was no witch. She was an abortion provider almost two centuries ago, infamously dubbed the “Wickedest Woman in New York” due to her services.[2] Despite her notoriety, Madame Restell’s practice shows just how prevalent the issue of abortion has been over time. Abortion is defined as the intentional termination of a pregnancy and, as far back as 1550 BCE, humans have managed unwanted pregnancies by obtaining abortions. [3] The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reported about 620,000 abortions in 2020, or roughly 11 abortions for every 1,000 women ages 15-44. [4] The legality of abortion in the United States used to be protected under Roe v. Wade (1973), but after the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), Americans no longer have a federally protected right to abortion under the U.S. Constitution. This new ruling upended 50 years of precedent and triggered a wave of abortion bans across the country. As abortion becomes criminalized again in many states, it is imperative to understand the history of reproductive rights in the U.S. and the troubling legal concerns that arise in a post-Roe America.

The origin of Roe v. Wade can be traced back to 1969, when Norma McCorvey found out she was pregnant with her third child. After seeking out abortion options, she was referred to Linda Coffee and Sarah Weddington. [5] These two attorneys wanted to abolish the statute that criminalized abortion in Texas, so McCorvey agreed to sign on as their plaintiff in order to sue the state of Texas. [6] Under the pseudonym “Jane Roe”, McCorvey filed a class-action lawsuit against Henry Wade, the Dallas County District Attorney at the time. Roe claimed that the law in question—which made it a crime to “procure [or attempt to procure] an abortion” except if done under a doctor’s orders for life-saving circumstances—was unconstitutionally vague and violated her right to privacy under the First, Fourth, Fifth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments. [7] Meanwhile, the state of Texas asserted that there was a compelling state interest to restrict abortion in order to protect the health of pregnant people, as well as protect prenatal life from the moment of conception. [8]

Roe v. Wade went all the way to the Supreme Court, where the Court ruled 7-2 that the Due Process Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment contains a right to privacy which protects a pregnant individual’s choice on whether to have an abortion. [9] Since the Due Process Clause protects life, liberty, and property from being taken unlawfully, the abortion decision was deemed a private matter that—for the sake of liberty—should not be infringed upon. However, the Court did not grant an absolute right to privacy for pregnant individuals, which would have allowed abortions at any point in a pregnancy. Rather, the Court did agree with the state of Texas that, at some point, it had a compelling interest to regulate this right. During the first trimester of pregnancy, the state had no compelling interest in regulating abortion. During the second trimester, the state had a compelling interest in regulating abortion as it related to parental health because, at this point, the mortality rate from an abortion procedure exceeded the mortality rate from normal childbirth. [10] Regulations of this kind could include qualifications of the abortion provider, abortion facility standards, etc. During the third trimester, the state had a compelling interest in regulating abortion entirely because, at this point, the fetus has reached the threshold of viability—where it can survive outside the womb. [11] As such, the Court allowed states to ban abortions past the threshold of viability except in cases where the pregnant individual’s life was in danger. Meanwhile, Justice White’s and Justice Rehnquist’s dissents criticized the majority for their arbitrary trimester framework, which lacked constitutional foundation, and for overstepping into legislative decision-making rather than concentrating on the intent of the Founding Fathers who wrote the Fourteenth Amendment. [12] Furthermore, the dissenters' collective focus on consistent historical restrictions on abortion foreshadowed Roe’s overruling in 2022 for that precise reason.

After Roe, some states legalized abortion while others attempted to find loopholes to the ruling—many of which ended up in court. In fact, since Congress never codified Roe—meaning that the right to abortion never became federal law—this right has always been up to judicial interpretation. As such, a plethora of cases following Roe v. Wade gradually chipped away at abortion rights until Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) completely overturned Roe. This case was brought about because of Mississippi’s Gestational Age Act, which made it a crime to “intentionally or knowingly perform, induce, or attempt to perform or induce an abortion of an unborn human being” past the 15th week of pregnancy except in cases of “medical emergency” or “severe fetal abnormality.” [13] Jackson Women’s Health Organization sued Thomas Dobbs, Mississippi’s State Health Officer, to challenge the Act’s constitutionality. The organization claimed that the state had not proven that a fetus was viable at 15 weeks and that Supreme Court precedent in Roe did not allow states to ban abortion prior to fetal viability. [14] The Mississippi Legislature, in justifying the Act, asserted that the state had a compelling interest in protecting unborn life against the dilation and evacuation procedure used in abortions after 15 weeks. [15]

As a consequence of polarized political ideologies seeping into the Court, the majority in Dobbs narrowly ruled 5-4 to overturn Roe v. Wade. The majority opinion relied on the framework from Washington v. Glucksberg (1997), where the Court held that physician-assisted suicide was not a constitutional right because it was not “deeply rooted in the Nation’s history and tradition.” [16] Applying that same standard to abortion, the Court conducted a historical analysis and found that, prior to Roe, there was virtually no legal support for such a right. On the contrary, abortion was criminalized for most of the nation’s history, even during the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment—the exact amendment from which Roe had derived the abortion right. [17] Furthermore, the Court argued that a right to abortion was not essential to the “concept of ordered liberty” because there was no order in circumventing the legislative process. [18] In trying to strike a balance between the interests of pregnant individuals and potential life, Roe imposed a specific valuation onto the entire nation and prevented state legislators from expanding or tightening abortion regulations as their voters saw fit. Finally, the Court remained unconvinced that an abortion right was connected to the broader right of liberty, as that argument could lead to a slippery slope of justifying a right to prostitution, illicit drug use, and other illegal actions. [19] The Court’s lengthy opinion ultimately concluded that abortion was no longer a constitutional right, which allowed the Mississippi Legislature—and any other state legislature—the power to legislate abortion as it saw fit.

Although the decision to overrule Roe was narrowly divided, the ultimate judgment in Mississippi’s favor was a 6-3 decision. Chief Justice Roberts concurred with the judgment, as he felt that Mississippi’s Gestational Age Act should have been upheld but not at the cost of overturning Roe. His concurrence argued that 15 weeks gave people enough time to decide how to handle their pregnancy, so the Court could have simply overturned the viability aspect of Roe’s decision while still maintaining the right to choose. [20] While Roberts concurred because he felt the Court went too far, Justice Thomas’ concurrence did not think the Court went far enough. Thomas believed that the only rights rooted in the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause were those that concerned procedural aspects of law enforcement and did not extend further. [21] As such, his concurrence advocated for the overturning of all cases with these seemingly-fabricated rights, including the cases which granted a right to same-sex marriage, a right to contraceptives, and a right to consensual non-procreative sexual activity — Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), and Lawrence v. Texas (2003), respectively. [22]

While the majority opinion assured that no other rights were at risk, the dissenters pointed out that all these rights were linked to the same framework and that, if one could fall, then so can the rest. Justice Kagan explained that abortion was rooted in the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of liberty, as carrying a pregnancy to term undoubtedly alters someone’s life course. [23] As such, safeguarding reproductive freedom ensured that pregnant individuals were not deprived of liberty, but rather given the opportunity to make this personal medical decision for themselves. With this majority opinion, however, states could now restrict abortion as they wished—regardless of the physical, emotional, or financial impact on the pregnant person. The dissent criticized the majority for pretending to be neutral, when in actuality “the Court acts neutrally when it protects the right against all comers” rather than allowing states to decide who has a right and who does not. [24]Ultimately, the dissent warned of the damaged integrity of the Court for overturning precedent for “no good reason” and foreshadowed the harm that would come to those attempting to exercise reproductive rights when abortion is completely criminalized in their state. [25]

Anticipating the demise of Roe, 13 state legislatures passed “trigger laws” that would immediately criminalize abortion if the Supreme Court overturned Roe. Those laws went into effect after Dobbs was announced, with some states banning abortion at the moment of conception and without exceptions for cases of rape, incest, or serious health risks to the pregnant person. [26] The penalties for violating abortion bans can be as severe as a $100,000 fine and a life sentence in prison, as well as loss of medical license for abortion providers. [27] There have also been attempts to include “bounty hunter” provisions that allow individuals to sue abortion providers and receive damages, but they were struck down due to issues of constitutionality—mainly revolving around vagueness and lack of standing. [28] While certain states have waged war against abortion, others have made it a point to enshrine the right to abortion in their state constitutions. Some states also have “shield laws” in place that provide safeguards for out-of-state patients who seek abortion services in protected states, as well as for their abortion providers within those states. Nevada’s shield law states that the governor will not cooperate with states that criminalize abortion in regard to issuing arrest warrants, surrendering information about someone’s visit to an abortion provider, or utilizing law enforcement to apprehend the individual. [29] Although shield laws certainly help, the financial burden of obtaining out-of-state reproductive care makes abortion beyond reach for many Americans, especially considering most abortion-seekers are low-income and abortions alone cost over $500—not including travel costs. [30]

In spite of this, states with abortion bans are still trying to extend those bans nationwide, criminalizing their residents for obtaining an abortion even in a different state. Idaho is the first state to attempt this so far, but its law only entails minors seeking abortions out of state. [31] Regardless, these laws have contradicting support from the U.S. Constitution, as Americans have a right to travel between states and states must respect the laws of other states while also not impeding interstate commerce. [32] There is a high likelihood that the Supreme Court may be asked to resolve this contradiction. Abortions via medication may seem more feasible considering its availability through the mail, but anti-abortion states are working to restrict that as well. Although mifepristone—the primary drug for inducing abortions—was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) back in 2000, the FDA recently created some restrictions to mifepristone’s accessibility. [33] As such, two separate lawsuits came about and required the FDA to somehow revoke its approval of mifepristone and lessen regulations regarding mifepristone’s availability. [34] Since there is a disagreement between two federal courts, the Supreme Court will likely be asked to rectify this issue as well.

Dobbs' most troubling consequence may be the confusion doctors face, which makes them hesitant to provide necessary care to pregnant patients. Physicians are so fearful of the legal recourse for performing an abortion that they wait until the symptoms are astronomically severe before providing reproductive healthcare, resulting in near-death experiences and long-term pregnancy complications. [35] Yet, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act of 1986 (EMTALA) requires medical professionals to provide stabilizing treatment in emergency situations, and violations of this federal law for the sake of statewide abortion bans are already being investigated in Missouri. [36] Amidst the legal limbo, pregnant people’s lives are at stake. Despite having good health insurance, expectant patients may be at risk for serious infections or extreme blood loss due to vague abortion bans and harsh penalties for violating them. In the worst-case scenario, a pregnant individual cannot seek medical help at all and will have to either succumb to fatal symptoms or resort to unconventional, life-threatening methods to terminate their pregnancy. Considering that the vast majority of people who obtain abortions are low-income, this future seems inevitable for anyone from an anti-abortion state wishing to terminate their pregnancy, regardless of medical necessity.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs produced more problems than solutions. Not only did the decision upend 50 years of precedent, but it also gave an avenue for the Court to rescind other rights that fall under the “privacy” umbrella. Moreover, the inconsistency across states’ abortion regulations creates inequity regarding access to reproductive healthcare—even in life-saving circumstances. The most harrowing aspect of this ordeal is that statewide abortion bans only force people to either travel to a protected state, if they have the means, or resort to unsafe methods of terminating their unwanted pregnancy. Criminalizing abortion does not stop abortions from occurring. [37] Given that financial concern is the biggest reason why people seek abortions, anti-abortion states would probably see more reduction in abortions if they provided better financial assistance to pregnant individuals. Increasing the amount of paid family leave, raising the minimum wage, or establishing a universal base income are just a few solutions that would drastically improve the financial situations of expectant people. Until then, the issue may only worsen, as the Supreme Court could hear cases in the near future regarding abortion bans’ legal contradictions. That said, while this current Supreme Court majority opposes abortion, a future Supreme Court could reverse Dobbs and repeat this cycle in another 50 years. The legal future of reproductive rights remains unclear, so until Congress establishes federal legislation regarding the matter, “[states] can force [people] to bring a pregnancy to term, even at the steepest personal and familial costs.” [38]

Sources

Horwitz, Rainey. “Ann Trow (Madame Restell) (1812–1878) .” The Embryo Project Encyclopedia, August 23, 2017.

Aliano, Kelly. “Life Story: Ann Trow Lohman, a.k.a. Madame Restell.” Women & the American Story, May 17, 2023.

Potts, Malcolm, and Martha Campbell. “History of Contraception.” The Global Library of Women’s Medicine, May 2009.

Diamant, Jeff, and Besheer Mohamed. “What the Data Says about Abortion in the U.S.” Pew Research Center, January 11, 2023.

Barnard, Christianna K., "Jane Roe Gone Rogue: Norma McCorvey’s Transformation as a Symbol of the U.S. Abortion Debate." Women's History Theses. May 2018.

Ibid.

Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

MS Code § 41-41-191 (2018)

Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022)

Ibid.

Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702 (1997)

Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022)

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Jiménez, Jesus, and Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs. “What Are Abortion Trigger Laws and Which States Have Them?” The New York Times, June 24, 2022.

Damante, Becca, and Kierra B. Jones. “A Year after the Supreme Court Overturned Roe v. Wade, Trends in State Abortion Laws Have Emerged.” Center for American Progress, June 15, 2023.

Ibid.

SB 131, 82nd Session (Nevada 2023).

Diep, Karen, Usha Ranji, and Alina Salganicoff. “Key Facts on Abortion in the United States.” KFF, May 11, 2023.

Hanna, John, and Geoff Mulvihill. “Next Abortion Battles May Cross State Borders.” AP News, April 10, 2023.

Ibid.

Sobel, Laurie, and Alina Salganicoff. “Q & A: Implications of Two Conflicting Federal Court Rulings on the Availability of Medication Abortion and the FDA’s Authority to Regulate Drugs.” KFF, April 8, 2023.

Ibid.

Simmons-Duffin, Selena. “Doctors Who Want to Defy Abortion Laws Say It’s Too Risky.” NPR, November 23, 2022.

Meyer, Harris. “Hospital Investigated for Allegedly Denying an Emergency Abortion after Patient’s Water Broke.” KFF Health News, November 1, 2022.

Biggs, M Antonia, Heather Gould, and Diana Greene Foster. “Understanding Why Women Seek Abortions in the US.” BMC Women’s Health 13, no. 1 (July 5, 2013).

Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. ___ (2022)

The Laws that Change America’s Health

One of the purposes of law in civil society is, arguably, to protect the general safety and welfare of all people. Laws that protect human safety may be associated with those that prevent bodily harm or wrongdoings such as robbery or murder. Bodily harm, however, can also be a result of unsafe practices such as the unsanitary handling of food. In that case, laws are developed and implemented to promote food safety. While associations with the law are not often correlated to healthcare, nearly all commonplace civilian protections towards health and safety are guaranteed to society through a specific area of the law – health law. As described by Harvard Law, “health lawyers work on cases and policy relating to access to care, insurance coverage, difficult ethical choices, providers of care, the safety of our drugs and food supply, disease prevention and treatment” and many other complex healthcare-related issues. As a result of health law and policies implemented over the last century, people can enjoy longer, healthier lives. The history surrounding this type of law has not always been constructive. In today’s world, there exist many laws and policies that govern the healthcare world that threaten to discriminate against members of society, subsequently worsening healthcare outcomes.

April 2023 | Kira Kramer (Staff Writer & Editor)

One of the purposes of law in civil society is, arguably, to protect the general safety and welfare of all people. Laws that protect human safety may be associated with those that prevent bodily harm or wrongdoings such as robbery or murder. Bodily harm, however, can also be a result of unsafe practices such as the unsanitary handling of food. In that case, laws are developed and implemented to promote food safety. While associations with the law are not often correlated to healthcare, nearly all commonplace civilian protections towards health and safety are guaranteed to society through a specific area of the law – health law. As described by Harvard Law, “health lawyers work on cases and policy relating to access to care, insurance coverage, difficult ethical choices, providers of care, the safety of our drugs and food supply, disease prevention and treatment” and many other complex healthcare-related issues. [1] As a result of health law and policies implemented over the last century, people can enjoy longer, healthier lives. The history surrounding this type of law has not always been constructive. In today’s world, there exist many laws and policies that govern the healthcare world that threaten to discriminate against members of society, subsequently worsening healthcare outcomes.

One aspect of health law that is incredibly fascinating is the overlap between this type of law and other areas of law that are utilized to craft health legislation. Some of the types of law that are utilized within health law include: “contract law, tax law, insurance and pension law, employment and labor law, public benefits law, torts, ethics, criminal law, administrative law, privacy, civil rights, reproductive rights, constitutional law, and statutory drafting and interpretation—even First Amendment religious liberty and freedom of speech concepts can be implicated in the field.” [2] Health law is practiced at every governmental level, from local government up to the national level, and even into the private sector. Different types of groups, from nonprofit organizations, private or public interest law firms, can practice health law. Some of the major issues that health law aims to address include access to healthcare, insurance, public benefits, provider behavior, cost containment, public health, bioethics, food policy and regulation, medical malpractice, and many more. While health law may seem like a very niche area of the law, it is deeply associated with the everyday lived experiences of many people. Everything – from access to clean drinking water to laws requiring that you wear a helmet while riding a motorcycle – has been regulated by the health law.

While health law incorporates vast specialties within the law, it also protects the health and well-being of citizens. Some of the most incredible accomplishments of health law include the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the subsequent legislative accomplishments that allowed for the regulation of “foods and prescription drugs; mandated folic acid fortification of cereal grain products; limits on chemical contamination of crops; food stamps; the Women, Infants, and Children program; and school meals” are measures that have improved the health and safety of Americans. After the publication of Upton Sinclair’s, The Jungle – which exposed the horrific working conditions in the meat-packing industry – laws and regulations were introduced to protect consumers from unsanitary food manufacturing practices. As a result of The Jungle, President Theodore Roosevelt passed a law regulating food and drugs on June 30, 1906. That same day, he also signed the Meat Inspection Act. This would eventually lead to the Pure Food and Drug Act, which regulates food additives and prohibits misleading labeling of food and drugs, as well as the formation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Today, the FDA is responsible for “protecting the public health by ensuring the safety, efficacy, and security of human and veterinary drugs, biological products, medical devices, our nation's food supply, cosmetics, and products that emit radiation.” [3]

Health law, however, has not always been as forthcoming or upstanding. Sometimes the law has been downright atrocious. At times, the purveyors of the legal system have enacted laws that actively harm the health and well-being of citizens. One of the most heinous examples takes place in 1927 when the Supreme Court decided to uphold a state's right to forcibly sterilize a person they considered unfit to procreate in a 8 to 1 vote. In Buck v. Bell (1927), a young woman named Carrie Buck, whom the state of Virginia had deemed to be "feebleminded” was forcibly sterilized against her will. [4] This ruling would lead to the forced sterilization of over 70,000 people in the 20th century. [5] Justice Holmes was able to rule using compulsory vaccination, validated under Jacobson v. Massachusetts (1905), to support the justification of forced sterilization. [6] He then verbally justified his decision saying that “three generations of imbeciles are enough.” [7] This was a major violation of human rights and a horrific failure of the public health law to protect the health of citizens.

The degree to which the government can intervene in the health of a person or community has not always been straightforward. The recent COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent vaccination requirements have spurred constitutional discourse about whether or not the federal and state governments are permitted to pass public safety policies that may or may not violate constitutional rights. There are two Supreme Court decisions that guide state and local authorities to issue vaccine mandates. In 1905, the Supreme Court ruled in Jacobson that “under a state law local health authorities could compel adults to receive the smallpox vaccine.” [8] The Court justified this decision by saying that under the state’s general police power there exists the ability to enact laws that protect the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the public.

In 1922, the second decision on vaccine mandates came as a result of Zucht v. King,where the Court reached a similar conclusion. Henning Jacobson and Rosalyn Zucht argued that the vaccine policy violated their 14th Amendment due process rights. Similar lawsuits that occurred during the pandemic still ruled in favor of vaccination mandates, stating that there is not enough evidence to support the argument that their constitutional rights are being violated by having to observe vaccine mandates. These mandates are made possible through Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA), which allows the Department of Health and Human Services or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to make necessary measures “to prevent the introduction, transmission, or spread of communicable diseases from foreign countries into the States or possessions, or from one State or possession into any other State or possession.” [9] However, federal laws provide protections to employees based on religious beliefs or disability status. Enacting a federal vaccine mandate would provoke legal challenges because the 10th Amendment prohibits commandeering or forcing states to use their own resources to carry out our federal policies.

Even though there are limitations to the extent to which the government can enact health policy, there are opportunities at the state level to enact laws that change the health of communities. There does not exist a universal healthcare system in the United States, therefore, each state is able to dictate different types of health and safety laws. There exists a handful of laws and policies in the world of healthcare that are enacted and enforced by the federal government. Some examples of these would be the enforcement of the Federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 (PSQIA), and fraud and abuse laws to name a few. [10] Despite these federal regulations, much of the public health law that governs peoples’ daily lives come from state legislators. Even though Medicare, Medicaid, Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and other federal programs were created by the federal government, the benefits and eligibility pertaining to each are decided differently by each state. This causes significant discrepancies and disparities between health access and coverage. Therefore, Health law advocates are siloed by the law and policy that exists in their state.

Despite the challenges that the fragmented system presents, it is still possible for individuals to influence policies that change the health outcomes of their communities for the better. Some of these changes can be sought out through the presentation of bills at the local, state, and national levels. Legislators can develop their bills from several different sources. These sources include constituents, legislative hearings, and personal experience as well as research on the idea (current Nevada law or other states). [11] There could also be a request for a bill draft resolution (BDR) or they have the option to have the Legal Division prepare the bill draft and deliver it to a sponsor (requestor). [12] This means that people personally affected by a health issue in the community can seek out their representatives and propose a bill that addresses a concern in their community. David Bandbaz did just that.

Bandbaz is a fourth-year medical student at the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine. In the spring of 2023, he matched with the University of Utah to attend their general surgery residency program. While on rotations in UMC’s trauma center, he would observe the grotesque injuries that patients would present as a result of motorcycle accidents. After becoming seriously injured in a motorcycle accident himself and researching the incidence and severity of motorcycle-related death and injury, he knew something needed to be done. Through collaborating with community partners and staff at the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine, he was able to work with Nevada State Senator, Dallas Harris, to propose a bill in the 2023 legislative session that aims to reduce the risk of death and injury in motorcycle vehicle accidents – SB 423.

One of the components of this bill calls for riders who were found riding without a motorcycle endorsement to undergo rider safety training within nine months of the date of the final order of the court in lieu of assessing the fine for the violation. [13] The bill also requests that motorcycle endorsements be renewed by retesting via taking a safety course, to prove that riders are still capable of riding a motorcycle. [14]Another component of the bill is that riders under 30 years old must complete a course of motorcycle safety in order to renew their endorsement at least once every 8 years after the initial issuance of the endorsement. [15] For riders over 30 years of age, this would be at least once every 12 years after initial issuance. SB 423 passed through the Senate Committee on Growth and Infrastructure and Assembly Growth and Infrastructure Growth Committee. It has also passed both the Assembly and State Senate as of May 25, 2023. Bandbaz has been working with legislators and community members on this bill for three years, and his dedication is a testimony to how individual community members can enact change.

Many public health laws are being presented at the 2023 Nevada Legislative Session. This is likely due to the fact that this is the state’s entire in-person session since the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic shined a spotlight on the deficiencies of healthcare systems across the country, and through law and policy, legislators and public health professionals can hope to improve access to healthcare, quality of care, and ultimately, health outcomes for all people. It is imperative to public health objectives that these initiatives continue to be prioritized and given adequate attention as time goes on, and as the memory of the pandemic fades from view. Due to global warming, overcrowding, and other modern-day issues, it is likely that pandemics and other infectious diseases will arise. Creating robust public health systems supported by law and policy will allow societies to be prepared for what the future holds.

Sources

Pattanayak, Catherine, Joan Ruttenberg, and Annelise Eaton. “Health Law: A Career Guide.” Bernard Koteen Office of Public Interest Advising. Harvard Law, 2012.

Ibid.

“Food and Drug Administration.” USAGov.

Buck v. Bell. 274 US 200 (1927).

The Petrie-Flom Center Staff. “Why Buck V. Bell Still Matters.” Bill of Health. Harvard Law Petrie-Flom Center, October 15, 2020.

Buck v. Bell. 274 US 200 (1927).

Ibid.

Bomboy, Scott. “Current Constitutional Issues Related to Vaccine Mandates.” National Constitution Center. August 6, 2021.

“42 U.S. Code § 264 - Regulations to Control Communicable Diseases.” Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law.

Kalantar, Art. “6 Key Laws That Regulate the Healthcare Industry?” Law Offices of Art Kalantar, June 12, 2020.

Malkiewich, Lorne, and Allison Combs. “The Nevada Legislative Process Lorne Malkiewich.” Nevada Legislature. Accessed April 20, 2023.

Ibid.

Nevada Legislature. Senate Bill NO. 423–Committee on Growth and Infrastructure. 82nd Leg. sess. Introduced in Senate March 27, 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.

The Fame in Defamation

Everything a celebrity does becomes part of the public eye in a matter of minutes. While celebrities try to keep their private life under wraps, the hopes of this happening usually fails. Pirates of the Caribbean star Johnny Depp and Aquaman star Amber Heard were no exception. Johnny Depp and Amber Heard have been caught up in a public scandal ever since their divorce in 2017. In the case of John C. Depp, II, v. Amber Laura Heard (2022), Johnny Depp (the plaintiff) sued former wife Amber Heard (the defendant) on grounds of defamation. Defamation is a false statement or claim that harms someone else’s reputation. There are two types of defamation – slander, which is in oral form, and libel, which is in written form. This accusation arose when Amber Heard wrote an op-ed for the New York Times. She wrote this article from the perspective of someone who was a victim of domestic abuse and later stated how she “felt the full force of our culture's wrath for women who speak out.” She never mentioned anyone by name in the article, but it was clear to Johnny Depp that it was about him…

April 2023 | Luke Slota (Executive Organizer) and Jesse Fager (Associate Editor)

Everything a celebrity does becomes part of the public eye in a matter of minutes. While celebrities try to keep their private life under wraps, the hopes of this happening usually fails. Pirates of the Caribbean star Johnny Depp and Aquaman star Amber Heard were no exception. Johnny Depp and Amber Heard have been caught up in a public scandal ever since their divorce in 2017. In the case of John C. Depp, II, v. Amber Laura Heard (2022), Johnny Depp (the plaintiff) sued former wife Amber Heard (the defendant) on grounds of defamation. Defamation is a false statement or claim that harms someone else’s reputation. [1] There are two types of defamation – slander, which is in oral form, and libel, which is in written form. This accusation arose when Amber Heard wrote an op-ed for the New York Times. She wrote this article from the perspective of someone who was a victim of domestic abuse and later stated how she “felt the full force of our culture's wrath for women who speak out.” [2] She never mentioned anyone by name in the article, but it was clear to Johnny Depp that it was about him. He then sued her for 50 million dollars on the grounds of defamation, specifically in the form of libel.

After over 3 consecutive years of trial, the jury reached a verdict in favor of Johnny Depp, entitling him to 10 million dollars in compensatory damages and 5 million dollars in punitive damages. Amber Heard on the other hand, filed a countersuit against Depp for 100 million dollars alleging that Depps' legal team falsely accused her of fabricating claims against the plaintiff. [3] The judges awarded Heard only 2 million out of the 100 million requested for the countersuit. Prior to the Virginia case, Johnny Depp sued The Sun in the U.K. over their claims that he is a wife beater. The judge ended up favoring The Sun, stating that what they put in the article was proven to be “substantially true”. [4] While this is the most well-known defamation case in history, there have been many cases in the past century.

Throughout the past century of defamation cases, the Supreme Court has attempted to find a fine line between defamation and freedom of speech. On one hand, defamation is a strong, yet necessary limitation on the first amendment, extending to both the freedom of speech and freedom of the press – without it, people’s reputations could be ruined. However, defamation suits could be seen as a limit of the first amendment if false accusations are made. It is extremely important to ensure that the defamation is either true or a case of ignorance – otherwise, anyone could say anything without punishment. This is why it is incredibly important to have a proper balance to set a precedent for future cases of defamation.

John C. Depp, II, v. Amber Laura Heard is a libel suit as Heard had written an op-ed for Washington Post about her experience with domestic abuse. Along with this, since this case is unique and between two celebrities, specifically public figures, there is an important standard to be established to file suit for libel. This legal standard is “actual malice” - requiring that the statement from the media defendant was made “with the knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” The burden of proof has a high threshold, requiring that there is “clear and convincing evidence” of actual malice. [5] Since public figures are often under high scrutiny from the public, it is important to protect them from criticism. Criticism is still an important right in the First Amendment. For example, if Amber Heard had a strong opinionated statement about Depp as her partner in the op-ed, she would have the right to do so and the libel suit would be ineligible. This right changes when an opinion becomes a false fact. Actual malice differentiates this threshold of harsh opinions from false facts.

This standard originated in the Supreme Court decision New York Times Co. v Sullivan (1964) in cases involving public officials. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court reversed libel damages filed by L. B. Sullivan, a city commissioner for Montgomery, Alabama. Before, libel suits were entirely under state law, making the difficulty of libel suits vary from state to state. In Alabama, the case was far too easy for Sullivan to win - all he needed to do was prove the existence of mistakes and how they harmed his reputation. [6] Had Sullivan won the libel suit, a precedent would have been set for future news outlets to chill public discourse against public officials. For the majority, Justice Willaim J. Brennan emphasized his point of concern by saying that “debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust and wide-open.” Future events protected by this decision include Watergate, the Iran-Contra affair, Flushgate, and more, which otherwise would have been impossible to publish. [7] Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts (1967) changed this standard to be extended to public figures, not just public officials, such as Heard and Depp. Wally Butts, an athletic director at the University of Georgia, was accused of match-fixing, an accusation that would surely hurt his reputation. The district court trial first found libel and the Supreme Court affirmed this ruling, but not without changing the standard to include celebrities, business leaders, and more. [8]

The past Supreme Court decisions definitely left a footprint in the John C. Depp, II, v. Amber Laura Heard. Being a public figure, Johnny Depp needed to prove the existence of actual malice for the defendant. The burden of proof makes it incredibly difficult for the prosecution to win - essentially, the prosecution must enter their mind in order to prove actual malice to the jury. This leans heavily in favor of the defendant since doing so can be a tall task, but was created to have a balance between defamation claims and the first amendment. Specifically, this standard would make suing the Post for the op-ed far more difficult. Firstly, there was no specific mention of Depp’s name, and secondly, Heard filed for a restraining order in 2016 which could protect the editors from being accused of actual malice since they had no reason for doubt of her abuse. However, suing Amber Heard was more straightforward. Firstly, her reference to “domestic abuse” essentially served to name Depp, and secondly, all Depp needed to prove was that she lied about her abuse which insinuates actual malice. Once the jury believed it was a fabrication, actual malice was satisfied and Amber Heard was found liable. [9]

Ultimately this case has left many major implications. One of the most prominent is that the verdict of this case could affect those who come forward about abuse, particularly against those in positions of power. especially against those who have a lot of power. Amber Heard has even expressed on social media that future victims may hesitate to speak up due to the repercussions. The case heavily impacted Johnny Depp and Amber Heard as the public is already seeing the negative consequences that arose from this case. Johnny Depps' reputation has been severely tarnished, losing roles in the Pirates of Carribean and Fantastic Beasts franchises, and Amber Heard has filed for bankruptcy in addition to her time in the upcoming Aquaman movie being cut down to just a few minutes. While this case did not lower standards for defamation cases against the press since Johnny Depp did not pursue that route, it has left many people confused as to whether or not it lowers the standards for future defamation cases against other people.

Sources

“Defamation.” Legal Information Institute, Legal Information Institute

Heard, Amber. “Opinion | Amber Heard: I Spoke up against Sexual Violence - and Faced Our Culture's Wrath. That Has to Change.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 2 June 2022

Chappell, Bill, and Jaclyn Diaz. “Depp Is Awarded More than $10M in Defamation Case against Heard and She Gets $2m.” NPR, NPR, 1 June 2022

“Johnny Depp Loses Libel Case over Sun 'Wife Beater' Claim.” BBC News, BBC, 2 Nov. 2020

Wermiel, Stephen. “Actual Malice.” Actual Malice,

Wermiel, Stephen. New York Times Co. v. Sullivan

Bertoni, Fabio. “Why the Washington Post Wasn't Named in the Johnny Depp–Amber Heard Trial.” The New Yorker, 3 June 2022

McInnis, Tom. “Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts.” Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts

Bertoni, Fabio. “Why the Washington Post Wasn't Named in the Johnny Depp–Amber Heard Trial.” The New Yorker, 3 June 2022

Russian Nuclear Weapons and the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

Speculations of potential nuclear warfare put global citizens at unrest and Russia's announcement of tactical nuclear sharing reminded the international world of destructive prospects anticipated in 2022. On March 25 2023, President Vladimir Putin publicly declared his intention to store Russian tactical nuclear weaponry in neighboring country and longtime ally, Belarus. Bilateral relations of Belarus and Russia have recently driven Belarusian support for the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Putin’s decision, announced late March, in no way, lessened nuclear tensions between the West and Russia. Though, the United States and Russia—once engaged in neutrality—signed the United Nations’ Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), international attention gathered once more following Russia’s announcement, drawing a question of whether or not weapon storage in Belarusian territory violates the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Both Belarus and Russia answered that it does not, citing the United States’ own power sharing agreement among North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries.

April 2023 | Mary Giandjian (Staff Writer & Editor)

Speculations of potential nuclear warfare put global citizens at unrest and Russia's announcement of tactical nuclear sharing reminded the international world of destructive prospects anticipated in 2022. On March 25 2023, President Vladimir Putin publicly declared his intention to store Russian tactical nuclear weaponry in neighboring country and longtime ally, Belarus. Bilateral relations of Belarus and Russia have recently driven Belarusian support for the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Putin’s decision, announced late March, in no way, lessened nuclear tensions between the West and Russia. Though, the United States and Russia—once engaged in neutrality—signed the United Nations’ Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), international attention gathered once more following Russia’s announcement, drawing a question of whether or not weapon storage in Belarusian territory violates the Non-Proliferation Treaty. [1] Both Belarus and Russia answered that it does not, citing the United States’ own power sharing agreement among North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) countries. [2]

Russia’s tactical nuclear weapon storage in Belarus incited international speculation. The Republic of Belarus’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared, “[t]he strategic partnership between Belarus and Russia is based on the geographic location, close historic and cultural links between both countries and peoples, economic ties and cooperation between the Belarusian and Russian businesses.” [3] At the beginning of the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War, however, Belarus worked to uphold relations with Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. A few days after the war’s commencement, a referendum in Belarus’ Parliament on February 27, 2022 saw to the constitution’s amendment in order to join Russian military operations. [4] Following Belarus’ switch to support Russia, it should be noted the two “have set up a joint regional military force” to “coordinate their air defense systems, perform joint military exercises, consider a number of questions regarding operative and combat training.” [5] Putin noted that ten Belarusian aircrafts have been upgraded to grant capabilities to carry nuclear weapons. The operations are said to begin April 7, Putin estimates the storage facilities, as well as Belarusian pilots and aircrafts, will be ready by July 1, 2023.

Knowing the operations to come, legality can only be assessed after examining the Non-Proliferation Treaty. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), signed in 1968 and put into effect in 1970, currently holds 190 Parties to the Treaty, following North Korea’s withdrawal in 2003. The Treaty’s objective reads: “to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.” [6] This treaty, the only multilaterally-binding agreement with the goal of disarmament, was extended indefinitely in 1995. Defined in the Treaty as having “manufactured and exploded a nuclear weapon or other nuclear explosive device prior to January 1, 1967,” the U.S. and Russia are two of five NPT designated nuclear weapon states. [7] Belarus, having joined the Treaty in 1994, declared itself among the non-nuclear states and ceded the nuclear missiles and weapons to Russia.

Governing sites from both parties involved have come forward in defense on the March 25 decision. Putin explained that the weapon sharing with Belarus was an anticipated response to Britain supplying armor-piercing shells to Ukraine amidst the war. The resulting controversy, as per President Putin, was a hypocritical backlash. Putin addressed the international community by citing the United States’ own nuclear power sharing agreement with Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Turkey under NATO. This power sharing agreement allows for the storage of roughly 100 American B-61 gravity bombs in said countries as well as necessary training in the case of deployment. Russia argues that the United States violated the 1968 treaty by distributing the nuclear weapons to European countries, clarifying that, “We [Russia] agreed that we will do the same – without violating our obligations, I emphasize, without violating our international obligations on the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons.” [8]

Belarusian president, Alexander Lukashenko, reinforced the statement made by Putin, clarifying that the agreed weapons storage cannot be considered a violation of the treaty since Belarus will have no authority or oversight to the weaponry. Yukashenko’s comment served as a reminder to the international community that the United States, in sharing nuclear weaponry with European states, remained in control of the distributed weapons. Similarly, Belarus will have no jurisdiction over Russian tactical nuclear weapons. Article I of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty restricts the transfer of weaponry, it reads:

“Each nuclear-weapon State Party to the Treaty undertakes not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly….” [9]

The defense testimonies by Putin and Lukashenko, while calling attention to the United States’ own decisions, bring forth a question of treaty enforcement: what can and will the international community do? To evaluate the present, a case of the past can be considered. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), also known as North Korea, joined the Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear state in 1985 and agreed to cease nuclear weapon manufacturing and allow for the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to perform inspections. [10] North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003 in pursuit of nuclear weapon manufacturing, with the argument that the United States was “threatening” its security by “hostile policy.” [11] North Korea, however, was permitted to withdraw from the NPT, as stated in Article X. The Treaty reads that parties, in recognition of national sovereignty, are able to withdraw from the Treaty in “extraordinary events, related to the subject matter of this Treaty, have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country.” [12] Each withdrawing party must give notice of such withdrawal to “all other parties to the Treaty and to the United Nations Security Council three months in advance. Such notice shall include a statement of the extraordinary events it regards as having jeopardized its supreme interests.” [13]

After providing a notice three months in advance, North Korea left the Treaty in 2003 after 18 years of membership. The North Korean case, therefore, serves as an example to the application of international treaties. While the withdrawal was valid under Article X’s conditions, the United Nations Security Council could have nonetheless ruled a threat to peace given the DPRK's explicit intent to resume missile testing. Under Chapter VII of the United Nations charter, the United Nations Security Council has the right to enforce “economic, diplomatic or even military sanctions” on North Korea. [14]

Besides North Korea, there has been a variety of non-compliance to the NPT that can also determine Russia’s future. Iran was another state seeking nuclear weapon capabilities, despite being a party to the NPT since 1970. In 2005, as it also concluded for North Korea, the IAEA found Iran in violation of the treaty’s safeguard, more specifically Article III. Iran disputed the uranium enrichment, the grounds for its violation accusation, by citing “peaceful” intentions under Article IV. The United Nations Security General at the time, Ban Ki-moon, had publicly displayed hopes for a resolution. Regardless, Iran faced sanctions for the treaty’s violation, some of which were imposed by former President Obama who expressed an intolerance for failure to maintain the obligations. Sanctions were then lifted from Iran by July 2015, but the path from noncompliance to consequence is one standing possibility for Russia if Putin’s claims become true in July 2023.

In the possibility of Russian non-compliance to the NPT, the other States involved have options of what to pursue. First, though the treaty is not immediately terminated upon breach, other parties involved may act as a continuing force, in which the legal obligations would continue or choose to terminate the treaty themselves. International treaties are upheld by the general will of parties involved – by consensus ad idem. Though the option of termination is available upon the necessary support, doing so has the potential to set a harmful precedent. To disband such an expansive, legally-binding agreement of nuclear deterrence would likely allow for nuclear developments. In this case, favor contractus, which describes greater benefit from continuing a contract over letting it expire, is supported by the “moral nature of international legal obligation” also known as pacta sunt servanda. [15]

The typical response to international treaty violations has been legal penalties and moral condemnation of guilty states. [16] Given the number of parties to the treaty, the ultimate jurisdiction resides with the United Nations Security Council as it could also apply sanctions or varying legal action to Russia if it determines that weapon storage was a violation of the NPT’s terms. While the treaty has no specification on exchanged weapons storage, the possibility of violation lies in Putin’s statement of training Belarusian servicemen to handle the newly stored weaponry. It must be noted that the situation following Putin’s March 23 declaration is full of uncertainty as the international community debates possibilities of tactical nuclear weapons actually being stored in Belarus. Prospective changes will not be fully understood until July 2023, the estimated time of completion as per Putin. The future of the matter residing with the United Nations, as written in the treaty, is one “considering the devastation that would be visited upon all mankind by a nuclear war.” [17]

Sources

Murdock, Clark A., Franklin Miller, and Jenifer Mackby. “Trilateral Nuclear Dialogues Role of P3 Nuclear Weapons Consensus Statement.” CSIS, May 13, 2010

Al Jazeera. “Why Does Russia Want Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Belarus?” Russia-Ukraine war News. March 28, 2023

“Belarus and Russia.” Belarus and Russia - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. Accessed April 27, 2023

Mudrov, Sergei A. “‘We did not unleash this war. Our conscience is clear.’The Russia–Ukraine military conflict and its perception in Belarus. Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe.” 30:2, (2022). 273-284, DOI: 10.1080/25739638.2022.2089390

“Belarus and Russia.” Belarus and Russia - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus. Accessed April 27, 2023

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed April 27, 2023

Ibid.

Al Jazeera English. “Ukraine Says Russia ‘Took Belarus as a Nuclear Hostage.’” YouTube, March 26, 2023

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed April 27, 2023

Bai, Su. “North Korea's Withdrawal from the NPT: Neorealism and Selectorate Theory.” E-International Relations, January 28, 2022

“North Korea's Withdrawal from the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty.” American Society of

International Law, January 24, 2003

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed April 27, 2023

Ibid.

Doyle, Thomas E. “The moral implications of the subversion of the Nonproliferation Treaty regime, Ethics & Global Politics, 2:2, 131-153, DOI: 10.3402/egp.v2i2.1916

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).” United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Accessed April 27, 2023

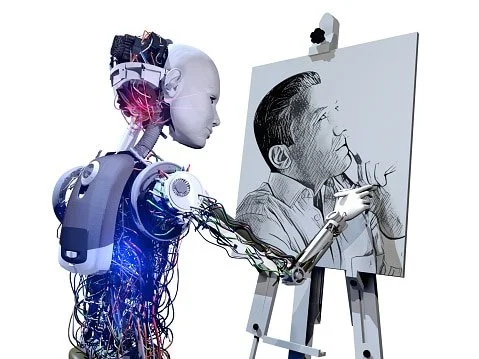

Monkey-ing Around: How One Monkey Shaped Copyright Law for Artificial Intelligence

“Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transcended its traditional role as a mere problem-solving tool, as it now produces stunning artworks, insightful essays, and soul-stirring music that rival those created by human beings.” The previous sentence was generated by an artificial intelligence bot, ChatGPT. Artificial intelligence has been top of mind since the rise of AI bots like ChatGPT. It has previously been used to screen job applications and make video recommendations on sites like YouTube, but now, AI can generate essays, art, music, and more with a simple prompt, bringing up questions over ownership rights. What is the legal future of AI? Can AI have intellectual property rights over the art it creates? Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they used AI to create?

April 2023 | Annie Vong (Editor-in-Chief)

“Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transcended its traditional role as a mere problem-solving tool, as it now produces stunning artworks, insightful essays, and soul-stirring music that rival those created by human beings.” [1] The previous sentence was generated by an artificial intelligence bot, ChatGPT. Artificial intelligence has been top of mind since the rise of AI bots like ChatGPT. It has previously been used to screen job applications and make video recommendations on sites like YouTube, but now, AI can generate essays, art, music, and more with a simple prompt, bringing up questions over ownership rights. What is the legal future of AI? Can AI have intellectual property rights over the art it creates? Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they used AI to create?

Firstly, to define intellectual property (IP), it gives ownership to creative works and processes and has three main types: copyright, trademark, and patents. Copyright law started with The Copyright Act of 1976, [2] which gave IP rights to artistic, literary, or intellectually-created works. Copyright differs from patents – which gives IP rights to technical inventions – and trademark – which gives IP rights to words, phrases, or designs. [3] Regarding copyright, the U.S. is one of many countries to adopt copyright law with the Berne Convention, which states that as a work of art is written, documented, or recorded physically, the creator of that work has automatic copyright, meaning that creators do not need to file any official forms to have copyright. [4]

Part One: Can Artificial Intelligence have Copyright?

The precedent for whether AI can have copyright emerges from Naruto v. David Slater et al, a case involving a monkey taking a selfie in Sulawesi, Indonesia. [5] Wildlife photographer, David Slater, left his camera unattended near the black macaque exhibit and a monkey named ‘Naruto’ took a selfie with his camera. Slater later published these photos in a photobook, claiming copyright only for himself. [6] People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), an animal rights organization, [7] sued on Naruto’s behalf for copyright infringement, arguing that because the monkey took the selfie by itself, Naruto is the creator of the work; therefore, Naruto has copyright due to the terms from the Berne Convention. [8] (Using the courts to secure rights for animals is not new; the courts have been used in an attempt to secure bodily autonomy rights for an elephant in the Bronx Zoo.)[9] Additionally, the Copyright Act defines five rights that copyright holders have, but does not explicitly define what authorship entails. PETA argued that the term “authorship” in the Copyright Act is up to interpretation. [10] For PETA, expansion of copyright ownership to animals can set precedent for animals to have other rights as well. And so, the courts had to decide the following issue at hand: Who owns copyright? Can a non-human creator own copyright?

The defendant, Slater, argued that he owned the camera equipment and that he created the situation that resulted in the picture being taken. For example, he checked the angle of the shot, set up the equipment, adjusted exposure, etc. He also argued that he has standing whereas Naruto did not. Who the court decides to give copyright to significantly impacts Slater's photography business, however, Naruto is not financially impacted at all if copyright is granted or not. The court ruled against PETA and Naruto citing their lack of standing. The district court reasoned that because the Copyright Act does not extend copyright to animals explicitly, the law does not apply to Naruto and that both PETA and Naruto were legal strangers to the case. [11] If a human were to file a copyright infringement suit on behalf of AI, that suit would likely also be dismissed as well on the same grounds. However, unlike Naruto, if AI were to ever represent itself in court, the court may find that it is not a legal stranger to the case and has standing.

After PETA and Naruto’s loss at the district court level, PETA appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the district court’s decision and emphasized that PETA and Naruto did not have standing to file for copyright infringement. They interpreted that the authorship under the Copyright Act specifically referred to “persons” or “human beings” and that Naruto did not fit under either category. [12]

The emphasis on “persons'' holding copyright brings up the philosophical question of what counts as a “person.” Must a person have consciousness? Intelligence? Must a person be of the human race? At what point can AI cross that threshold into being considered a person? Legally, the courts have extended the definition of “persons'' to include non-human entities before. For example, in common law, courts have ruled that the Catholic Church has the right to sell property. [13] Furthermore, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), the Supreme Court has granted corporations personhood and ruled that they can refuse to follow a federal healthcare mandate covering birth control if that mandate violated their religious exercises. [14] And, in Citizens United v. FEC (2012), the Supreme Court ruled that corporations have the right to freedom of speech via campaign contributions. [15] However, it can be argued that these groups (the Catholic Church, Hobby Lobby, and Citizens United) are collections of human members, and that AI is not, making them more different than similar to these groups that have gained rights through the courts. As rights for corporations have expanded, one question remains unexplored — can corporations who use AI as a tool to generate works of art have copyright? Can humans who use AI as a tool to make music have copyright?

Part Two: Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they create?

In April, a social media user named, “Ghostwriter977” posted a song that claimed to be crafted using AI. [16] The song, “Heart on My Sleeve,” used the likeness of two pop stars, Drake and The Weeknd. Universal Music Group (UMG), a corporation that owns the music label that Drake and The Weeknd have signed under, have filed a copyright claim taking down all posts containing this song. [17] UMG put out a response, “the training of generative AI using our artists’ music represents both a breach of our agreements and a violation of copyright law.” [18] Does UMG have grounds to copyright this song, even though it was not produced by Drake and The Weeknd themselves? To understand this, consider a scenario where AI was not used at all. Under the Copyright Act, use of copyright material is permitted in some cases such as in training, education, commentary, parody, etc. [19] If it is used (for example, if it is used in a parody or commentary) there must be some modification, transformation, or addition to the copyrighted material in order for it to constitute as fair use. It cannot be an exact copy of the material.

There exists an argument that Ghostwriter977 did not use any existing copyright material (or any other published songs) in the song itself, so it constitutes as a fair use of copyrighted material. But, on the other hand, there also exists an argument that Ghostwriter977 was using published songs (copyrighted material) to train the AI and used Drake and The Weeknd’s likeness to make a profit from the song. It can be argued that even if Ghostwriter977 used copyrighted material to train the AI, the song is transformative enough to count as fair use. It is still unknown whether courts will accept the argument that using AI as a tool in creating works of art is enough for the human creator to have copyright.

All of these cases pertaining to AI and intellectual property rights pose giant questions in copyright law. Drawing from Naruto, courts would most likely decide against artificial intelligence having copyright, but issues with copyright and AI move faster than the creation of legislation, and courts are forced to interpret law where law doesn’t exist, which can lead to a vulnerability in copyright law where it only takes one case to change the future of copyright for non-human entities forever.

Sources

“Introducing ChatGPT.” OpenAI

United States Congress. The Copyright Act of 1976. 94th Congress, Introduced

in Senate 15 January 1975. Pub. L. 94–553

“Trademark, patent, or copyright.” United States Patent and Trademark Office

“Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works” World Intellectual Property

Organization

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

O’Donell, Nicholas. “Is the ‘monkey selfie’ case making a monkey out of the law?”Apollo

Magazine. July 28, 2018

“About PETA: Mission Statement.” PETA

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

Lissett, Jenifer. “The Legal Rights of the Elephant in the Room.” UNLV Undergraduate Law

Review. February 2022

“UPDATE: ‘Monkey Selfie’ Case Brings Animal Rights Into Focus.” PETA, January 6, 2016

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

Ibid.

Totenberg, Nina. “When Did Companies Become People? Excavating The Legal Evolution.”

National Public Radio. July 28, 2014

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, 573 U.S. 682 (2014)

Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

Pahwa, Nitish. “How Two Music Legends Found Themselves at Some Anonymous TikTokker’s

Mercy.” Slate. April 17, 2023

Ibid.

Ibid.

“U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index.” U.S. Copyright Office. February, 2023

Bankruptcy Uncoded: The Biden Administration's New Changes

Student loans are a staple of higher education in this era. 43.5 million borrowers alone have federal student loan debt. The amount of student loan debt in 2022 was $1,757,200,000,000, and the average amount of student loan debt is $37,574 per student borrower. Furthermore, the average public university student will take out a whopping $31,410 to obtain their bachelor's degree. All of these numbers reveal the massive amount of debt that students in the United States incur to attend school. Many of them will not go into million-dollar careers, leaving them to spend their adult lives paying off student loans. Given the enormity of this issue, borrowers push for federal student loan forgiveness programs—but most of the laws do not come off the ground…

February 2023 | Jenifer Lissett (Staff Writer and Editor)

I. Introduction

Student loans are a staple of higher education in this era. 43.5 million borrowers alone have federal student loan debt. [1] The amount of student loan debt in 2022 was $1,757,200,000,000, and the average amount of student loan debt is $37,574 per student borrower. [2] Furthermore, the average public university student will take out a whopping $31,410 to obtain their bachelor's degree. [3] All of these numbers reveal the massive amount of debt that students in the United States incur to attend school. Many of them will not go into million-dollar careers, leaving them to spend their adult lives paying off student loans. Given the enormity of this issue, borrowers push for federal student loan forgiveness programs—but most of the laws do not come off the ground. This article will explore one new avenue for borrowers to discharge their student loans via bankruptcy. Section II will define the basics of the U.S. bankruptcy code. Then, Section III will shift to defining the previous standard before the Biden Administration changed their guidelines of federal student loans and bankruptcy. Finally, Section IV will detail the Biden Administration’s guideline changes to bankruptcy and federal student loans.

II. What is a debt and how does bankruptcy get rid of it?

According to 11 U.S. Code § 10—the set of U.S. laws that govern bankruptcy proceedings—a debt is a “liability on a claim.” [4] To further clarify, a liability is used in a context where there is a risk in entering into a contract. For example, a creditor, or someone who loans a consumer money, enters into a contract where they face a loss if the consumer does not pay back the debt. [5] Although, a debt is more inclusive than this and can involve a consumer owing money to a friend or family member. A contract is not a required feature to owe someone a debt.

These types of debts are considered consumer debts, or, in other words, these are not associated with businesses. Everyday people take out loans, charge purchases to their credit card, or borrow money from an acquaintance. If people become incapable of paying these debts, consumers can file for Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcy to discharge, or end their liability, in order to pay the debt back to the creditors. [6] Moreover, if a consumer cannot pay these debts back, it is fairly easy within the bankruptcy code to discharge them.

A consumer also has to pay attention to the distinction between an unsecured debt and a secured debt. Most consumer debts listed above fall under the unsecured loan bracket, as these debts do not have any physical property attached to them. [7] For example, a car loan or mortgage is a loan that is secured because there is physical property attached to the loan. The bank or lender has ownership of the property until it is paid off. On the other hand, credit card debt or payday loans are unsecured because there is no property attached to the loan. In those cases, a bank lent money to a consumer under the knowledge that it would be a standard loan with the expectation that it would be paid back. [8]

III. Student Loans and How it Differs.

Student loans in bankruptcy are more complex to discharge than regular unsecured consumer debts. Consumers have to go through a tedious system to try and meet a difficult standard of “undue hardship.” Undue hardship is an ambiguous standard that does not have a set definition. [9] One consumer can meet the standard by having constant medical debt; however, in a different district, another consumer who is in a similar situation may not meet this standard. In some states, it is up to consumers to prove a “certainty of hopelessness,” which is an extra burden in addition to proving undue hardship. [10] As a result of this vague standard, most student loans are not discharged in bankruptcy.

Previously, when a consumer wanted to discharge a student loan in bankruptcy, they would have needed to initiate an adversary proceeding against the student loan provider. [11] An adversary proceeding is, essentially, a lawsuit tried in bankruptcy court. [12] A consumer sues their student loan provider and fights their student loan at the adversary proceeding. [13] This process is costly to the consumer, though, as they will have to hire private attorneys to represent them. Consumers also have to fight against the seemingly endless onslaught of paperwork from the student loan provider’s legal team.