Neo Brandeis and the Broader Role of Antitrust in Preserving Democratic Health

August 2023 | Otoniel Ramos (Staff Writer & Editor)

Hunched over the illumination provided by gas light, Louis Brandeis struggled. His eyesight had begun to worsen, the large volume of required reading for his legal studies and the poor illumination provided by those same gas lights had taken their toll. [1] In his legal practice, Brandeis would earn the label of “The People’s Lawyer,” successfully leading fights to maintain public control of Boston’s transportation, consolidate the utility companies in the area, and even began to promote the idea of state unemployment insurance. [2] The case of Muller v. Oregon (1908) would see Brandeis’ first appearance before the United States Supreme Court; it is before this courtroom that Brandeis would provide a brief relying more on social and scientific data than on legal citations. [3] Later known as the Brandeis brief, this style of briefing before the Court would play a major role in cases like Brown v. Board of Education (1954), [4] where the need to demonstrate the harm of segregated education was paramount. [5]

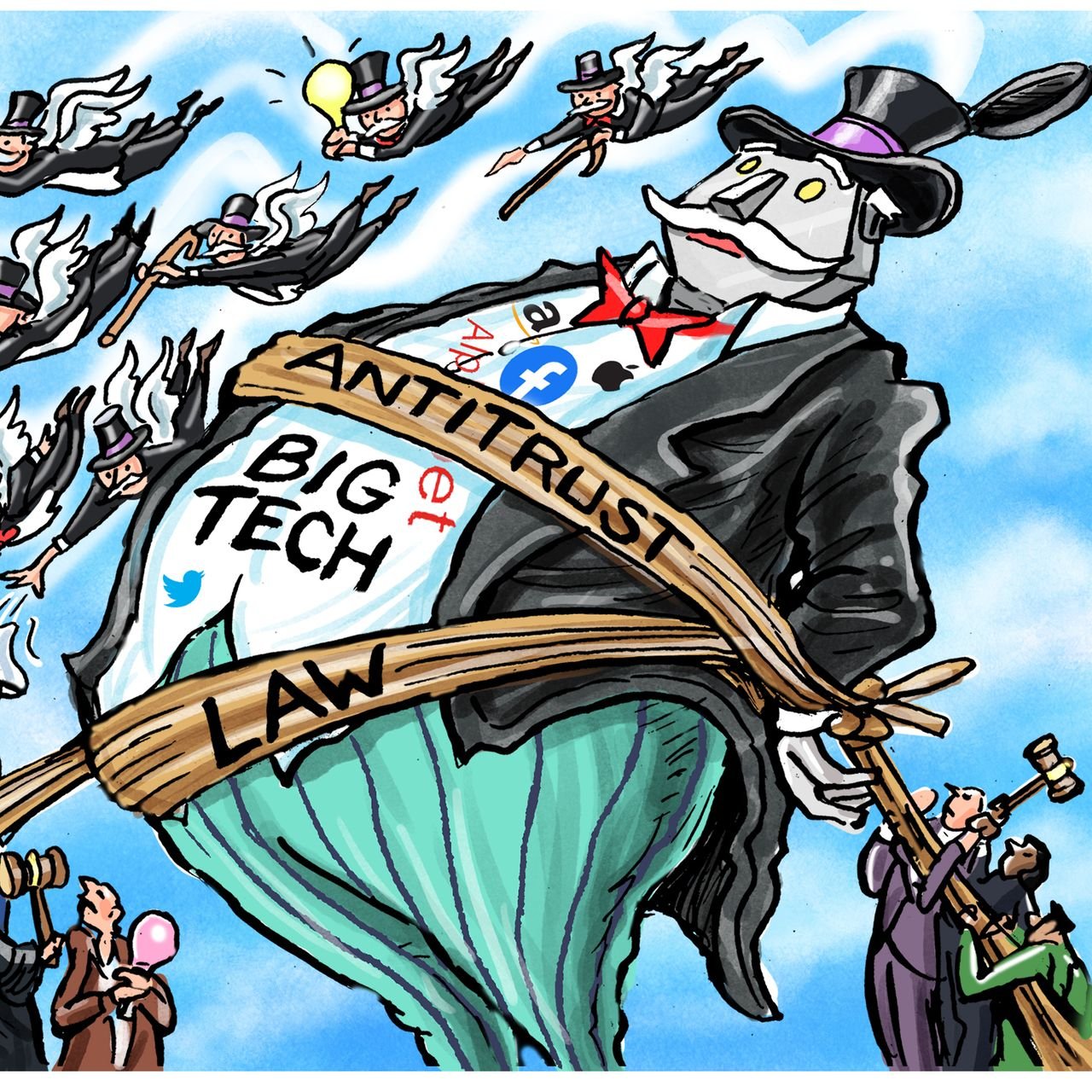

An important component of Brandeis’ advocacy revolved around his battle with J.P Morgan, at that time a railroad magnate—making fortunes reorganizing and consolidating railroad companies. Brandeis warned of the “Curse of Bigness” and the threat of concentrated economic power. [6] This article attempts to look at how the ongoing concentration of private economic power in our present decade has damaged the social, legal, and economic conditions necessary for a healthy democracy and the Neo-Brandeis. The past few decades have been marked by the massive growth in size and influence of tech corporations like Google, Meta, and Amazon, and the decrease in options available to consumers when it comes to grocery goods, event ticket providers, and even cable TV services. It is important to look at the effectiveness of current antitrust laws and enforcement as well as their role in this trend towards consolidated market power and the effects this has on levels of economic inequality, corporate political influence, and regulatory capture.

While it may be true, as stated by author Herbert Hovenkamp that concentrations of economic power have been “...the greatest engines of economic growth in recent history,” [7] their impact on levels of economic disparities, corporate political influence, and regulatory capture do more harm than good to the social, legal, and economic conditions necessary for a healthy representative democracy.

Understanding the Neo-Brandeis Antitrust Movement

Neo-Brandeisian policy calls for a broader interpretation and stronger enforcement of antitrust laws. Neo-Brandeisian policy possesses with it a strong and binding commitment to reducing the growing power of large corporations, which undermine the political self-determination of a country’s citizens. [8] Looking past what has been the standard of assessing harm to consumers, such an approach to competition policy intends to mitigate damage concentrations of market power may also pose to smaller businesses, smaller farmers, and labor. [9] Importantly, looking past strictly economic factors for antitrust regulation, Neo-Brandeisian policy directs attention to more social and political considerations for the application of antitrust policy. [10] Antitrust, as the next section of this article will address, has always had shifting political perspectives—often guided by contemporary economic/labor conditions. One cannot, however, disregard the intentions of antitrust legislation to subvert corporate political power. [11] In this regard, a neo-Brandeisian approach intends to impose a strict prohibition on the oligarchization of the country's political institutions. [12] Antitrust legislation in general has in one form or another been intended to function along some of the principles above mentioned. However, among the most unmistakably Neo-Brandeisian positions on competition policy are (1) a firm “opposition to economic concentration,” regardless of market efficiencies such a concentration would produce, (2) an opposition of vertical integration (in general), and (3) perhaps among the most “radical” of Neo-Brandeisian positions is the support for collective action by small business and workers to balance bargaining dynamics. [13]

Opposition to Neo-Brandeis

Ongoing debate exists around whether or not Neo-Brandeis is a viable or even the correct solution to the increased concentration of market power in today’s world. The most conservative of positions, with regard to the manner in which antitrust rules are applied today, is the position held by the ‘Chicagoans’ or the Chicago school of thought. [14] The more conservative position (not referring to partisan) argues that antitrust rules as they are today are enough and to redesign and reform them in their entirety poses harm to innovation, economic efficiency, and, interestingly, consumer welfare. [15] Much of the Chicago school of thought is influenced by the writings of Roberk Bork and Ward Bowman in ‘The Crisis of Antitrust’ (1965), in which the assertion is made that special considerations for small businesses or for the “inefficient” was not the intent of legislation such as the Sherman Act. [16] The strongest of assertions is that antitrust, as social policy, is incompatible with rules that promote competition. Such a balancing act and the courts’ attempts to fulfill the intentions of Congress would render antitrust cases a toss-up. [17] The view, however, of efficiency as the goal of competition, as many Neo-Brandeis scholars write, presents a “grotesque distortion of antitrust laws passed by Congress.” [18] A primary position in the advocacy of the Chicago School of Thought is to limit the power of antitrust law but to also limit the accessibility of relief for plaintiffs. [19] The middle ground, or “reform centrist camp,” as they are referred to by Professor Daniel A. Crane, seeks to address this aspect of antitrust, increasing the access of plaintiffs to relief. [20] Like the Chicago School, the reform centrist camp values efficiency and consumer welfare; [21] it is here where the biggest split between the reform centrists and Neo-brandeisians lies. While the regard for economic efficiency and consumer welfare is a strong position within the reform centrist camp, this same consumer welfare standard and the goal of protecting economic efficiencies are, for the Neo-Brandeisians, the fundamental problem with antitrust enforcement. [22]

The turn to the thoughts of Justice Louis Brandeis, then, is not unwarranted. Brandeis had, after all, spent most of his career practicing business law. He appreciated the goods a business could provide for its customers and the benefits of growth at a human scale, which at the time, that growth characterized American business and American farms. [23] Nonetheless, Brandeis was still weary of the ongoing trend of massive mergers and consolidations. In his battle against J.P Morgan and the New Haven Railroad, Brandeis railed against the problem of “excessive bigness.” [24] For Brandeis, the ongoing aggressive campaign to consolidate entire sectors of industry and these new businesses now characterized by massive mergers represented a “house of cards.” [25] Brandeis would later comment:

“We are in a position, after the experience of the last twenty years, to state two things: In the first place, that a corporation may well be too large to be the most efficient instrument of production and of distribution, and, in the second place, whether it has exceeded the point of greatest economic efficiency or not, it may be too large to be tolerated among the people who desire to be free.” [26]

It is here where Neo-Brandeis ideas begin to take shape. That despite a large business being at the point of greatest economic efficiency, it is enough justification against its existence if its size, influence, and power is not tolerated by “people who desire to be free.” [27] Indeed the uniquely Neo-Brandeisian political considerations in competition law are influenced by Brandeis’s belief that concentrations of power either market or governmental were detrimental to a people’s freedoms and insensitive to their fears. [28]

Historical Context: Government-Business Relations and the Threat to Democracy

The legal history of antitrust in the U.S. began with the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. [29] Later acts such as the Clayton Act of 1914 [30] and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 [31] represent a legislative effort to thwart the threat of concentrated market power and demonstrate a recognition these legislators had of the threat monopolistic power had on American liberties. [32] The threat to self-determination and the ability of Americans to decide the direction of their political future has always been an element of antitrust legislation. For example, The Celler-Kefauver Act passed in 1950 with the intention of strengthening the Clayton Act. [33] This act, often referred to as the “anti-mergers” act, was brought forward given its sponsors’ recognition that a lack of ability to control “economic welfare” was invariably linked to an eventual need for public seizure once a market concentration became too large and too powerful. [34] Such a seizure, warned Senator Kefauver, resulted in a Fascist state or the nationalization of industries. [35]

However, the history of American opinion on antitrust has often been influenced by the economic and labor conditions of the time. For instance, one can look at the Supreme Court from the end of the 19th and start of the 20th century. The Supreme Court of that era, according to author Robert G. McCloskey, had been hijacked by and made sacrosanct the principle of laissez-faire to the extent it was willing to question the legislature on issues of social policy. [36] The Lochner era, for example, represents an era of jurisprudence marked by arbitrary restrictions against government regulation. [37] Cases like Lochner v New York (1905), in which the Court struck down a maximum hour law for bakers, cited a new principle of “liberty of contract” between an employee and their employer. A later case, Bunting v. Oregon (1917), [38] illustrated these arbitrary restrictions clearly. [39] The case of Bunting, which posed a similar question before the Court— a maximum hour law for men and women was challenged on the basis that such a law infringed on the “liberty of contract.” The law in Bunting was upheld and decided entirely differently from Lochner. [40] The Court, essentially creating a parallel and dual precedent, fashioned for itself the tools necessary to decide as it wished on questions of regulation. While these cases represented a broader trend of what interpretation of the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment would begin to mean, the commerce clause had already, in essence, been hijacked by the ideologies of laissez-faire. [41] The case of U.S v. E.C Knight Co. (1895), for example, brought before the Court a question surrounding the application of the Sherman Antitrust Act against E.C Knight, a company with control of 98% of sugar refining in the country. [42] In its decision, ruling against the government, the Court ruled that (1) manufacturing was not commerce and (2) that the Sherman Antitrust Act “did not reach the admitted monopolization of manufacturing.” [43]

In stark contrast to said era, the period of World War II and up the 1960s was marked by a much different understanding of the role of antitrust. Congressmen such as Carey Estes Kefavuer understood that the Nazi totalitarianism that had taken hold in Germany could be attributed to the concentrations of economic power that had taken place in the preceding decades. [44] Such was the case that antitrust laws by the 1960s had been proclaimed an essential part of any functioning democracy. [45] If one takes a look at the case of United States v. Columbia Steel. Co (1948), [46] Justice Douglas’s words, in his dissent, paint a clear picture of what antitrust laws meant during that era and what they were intended to accomplish:

“The philosophy of the Sherman Act is that it should not exist, for all power tends to develop into a government in itself. Power that controls the economy should be in the hands of elected representatives of the people, not in the hands of an industrial oligarchy. Industrial power should be decentralized. It should be scattered into many hands so that the fortunes of the people will not be dependent on the whim or caprice, the political prejudices, the emotional stability of a few self-appointed men. The fact that they are not vicious men but respectable and social-minded is irrelevant. That is the philosophy and the command of the Sherman Act. It is founded on a theory of hostility to the concentration in private hands of power so great that only a government of the people should have it.”

It becomes apparent then that the common law history of antitrust is a substantial aspect of it. [47] The Chicago School of thought during the late 70s was able to convince the Supreme Court, based on its rulings in the 1940s and 50s, to “correct course” and rely on strictly economic factors—arguing that this posed no threat to market power. [48] Evidence of this is laid out in the case, Morrison v. Murray Biscuit Co. (1986), [49] in which Judge Posner asserts:

“To answer a question about antitrust as about any other field of law, it is always helpful and often essential to consider what the purpose of the law is. The purpose of antitrust law, at least as articulated in the modern cases, is to protect the competitive process as a means of promoting economic efficiency.” [50]

This trend from the 1970s to today, largely influenced by the Chicago school of thought and the broader Adam Smith laissez-faire ideals, marks once again a drastic shift in our interpretation of antitrust law. For Federal Trade Commission (FTC) chair Lina Khan, “We have shifted from a republican theory of antitrust to a neoliberal one.” [51] For example, in a more recent case, Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko, [52] a case on Verizon’s refusal to deal with a competitor, Justice Scalia’s words drastically move away from those that Justice Douglas had delivered some 50 years ago. In his opinion, Justice Scalia contends that the ability of a company to hold monopolistic power is (1) “not unlawful” but also that it is (2) “an important element of the free-market system.” [53] Some may, rightfully, make the claim that these are the words of one of the most conservative Justices that has sat on the Supreme Court, [54] but the ruling in this case, however, was unanimous. [55] Scalia’s opinion was additionally joined by 5 other Supreme Court Justices, including Breyer and Ginsburg. [56] In his opinion, Scalia adds:

The opportunity to charge monopoly prices—at least for a short period—is what attracts “business acumen” in the first place; it induces risk taking that produces innovation and economic growth. To safeguard the incentive to innovate, the possession of monopoly power will not be found unlawful unless it is accompanied by an element of anticompetitive conduct. [57]

This trend then, away from the view that concentrations of economic power pose a substantial threat to people’s freedom and the social and economic conditions of functioning democracies, threatens to replace the quite clear intentions of Congress, with an economic interpretation of the benefits a monopoly might provide. [58] [59] Legislative history up until the 1950s, with the amendment to Section 7 of the Clayton Act, had unequivocally rebuked the elimination of small business and entrepreneurship at the hands of concentrations of power and massive corporations. [60] Such a shift marks a stark disregard, not only for this legislative history, but for its intention to subvert the threat of concentrations of private market power to democratic health.

The Neo-Brandeis Approach: Addressing the Harms of Centralized Private Power

The departure of the Neo-Brandeisian approach from a strict emphasis on the standard of consumer welfare and economic efficiency, as the courts have largely established, is the strongest indicator of its departure from traditional approaches to antitrust. This position, however, is not without reason. Economic prosperity has not entirely followed an increase in market power since the broad adoption of the Chicago school of thought within courts. [61] It is also the case that the U.S. has additionally seen a decline in the growth of private labor productivity and multifactor productivity (MFP) since the start of the 21st century. [62] This report, in attempting to discern a decline in productivity, recognizes “barriers to competition” among other factors as an explanation for a decline in concentrated productivity growth. [63] It is clear that the allowance of market concentration has resulted in quite the opposite of what the Chicago school had intended. The idea that market forces and laissez-faire are a safeguard against monopoly and lead to economic efficiency, which should be rewarded and not stifled, leaves much to desire in the form of cooperative evidence. [64]

Then, it becomes useful to look at precedent, which Neo-brandeisians have looked to repeal. With the Chicago school having recognized the importance of consumer protection, it would, of course, make sense for practices such as predatory pricing, refusal to deal, and exclusionary trade practices, among others, to be rightly considered to have met the burden of harm to consumers. [65] Predatory pricing involves the reduction of prices to a level unsustainable for competitors, in turn eliminating competition, expanding market power of a corporation and profit motivation for the practice. [66] The most recognizable example of this phenomenon is Amazon, which began much of its early years without turning a profit. [67] Amazon shareholders valued growth and integration into different sectors over profit. The idea was that such a practice would inevitably yield the profits they had hoped for.

A protection against predatory pricing, however, is not the precedent set by the case Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. (1993), [68] which Neo-brandeisians have called for legislative measures in efforts to repeal. [69] Brooke, contrary to the intentions of legislation such as the Sherman Antitrust Act, set two required bars a successful claim of predatory pricing must meet. First, the need to demonstrate the price set by the defendant or competitor was below cost, and second, the requirement that the plaintiff establish a “reasonable prospect” of recoupment by the defendant. [70] The Court, in its justification for setting up the below cost pricing requirement, argued as follows: that price cuts are “the means by which a firm stimulates competition,” and that so long as price was above cost, it would remain “desirable” and improve consumer welfare. [71] To condemn a price cut would “chill” the practice of cutting prices. [72] The Court argued that in ruling against Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. for predatory pricing, it would create potential for ”false condemnation” and discourage companies from undertaking price cuts. [73] This logic, as some Neo-brandeisians have pointed out, fails to consider that such a price cut with the potential to exclude a higher cost rival undermines competition. [74] The desirability of the price cut, which “antitrust laws are designed to protect,” as the Court ruled, is completely undermined by the elimination of competition whose presence would have acted as a check on the larger firm's prices. [75]

In turning to exclusionary and restrictive trade practices, the precedent of Ohio v. American Express Co. (2018) [76] also leaves much to desire for the Neo-brandeisians. [77] The case involved the anti-steering practices of credit card companies and their effects on trade restrictions, which came under scrutiny of the Sherman Antitrust Act. [78] The Court, in deciding this case, argued that because American Express and other credit card companies operate in two markets, that being the market for merchants and the market for cardholders, the burden was on the government to prove that the actions of Amex were anti-competitive in both (which they did not). [79] This ruling in setting up the “two-sided markets construct” would now require an antitrust plaintiff to establish the harm of anti-competitive behavior across multiple markets. [80] Neo-Brandeis scholars have contended that this precedent has important implications for the growing issue of platform monopolies. They argue that the same exclusionary practices the credit card companies were engaging in are similar to the ones adopted by Google, Amazon, Meta, and Apple to obtain their monopolistic power. [81]

The decision in Ohio, however, for even those in the moderate or reformist camp, represents a lack of recognition in the courts of an ever increasing market problem. [82] The inaction and the reluctance to revamp competition rules disregards the feelings around the country in favor of strong antitrust rules and enforcement. [83] The predatory pricing and exclusionary practices which have become widely adopted among the tech giants of today are a clear reflection of this inaction. Courts have increasingly adopted the mindset that judicial errors are much harder to correct than the anticompetitive behavior of a corporation. [84] [85] As Justice Neil Gorsuch during the oral argument for Ohio put it:

“Why shouldn’t we take Judge Easterbrook’s admonition seriously, that judicial errors are a lot harder to correct than an occasional monopoly where you can hope and assume that the market will eventually correct it? Judicial errors are very difficult to correct.” [86]

Precedent over the past 50 years, despite the perception of judges as to the effects (of it) and the increasing problem of market concentration, has thus left the courts with only the option of pushing competition rules further into the non-interventionist path. [87] Then, taking a look at the precedent set to this point, small steps can be taken towards protecting economic fairness and countering the effects of concentrated private power.

Contemporary Challenges and the Neo-Brandeis Response

Today, the purpose of antitrust laws, as they have been established by recent precedent, has been the promotion of economic efficiency. [88] But is this purpose and application of antitrust laws up to the task of addressing some of the important contemporary issues we face today? Among the issues that antitrust laws and their enforcement must begin to address are: (1) the increases in globalization and interdependence and the jurisdictional issues that accompany that, (2) the rise of platform monopolies, and (3) the protection of privacy and user data on digital platforms. First, the increase in globalization poses a very interesting issue of extending a nation's antitrust policies beyond its borders. In some instances, such an expansion of antitrust laws and the attempted application of said laws outside a nation's borders raises questions of national sovereignty. [89] For antitrust cases involving market integration across borders, the most pertinent question that arises is how to define the “relevant market.” [90]

The rise in platform monopolies has also seen increased attention, especially as public scrutiny of the tech giants of today has taken hold. Platform monopolies of our time, have had the unique advantage of benefitting from a lax understanding of antitrust laws set forth by the Chicago school of thought. [91] In recent years, they have been able to “exploit their positions as providers of multiple essential services to bankrupt, supplant, or sideline rivals in every market in which they operate.” [92] Microsoft for example has, for the past year, been the target of FTC action against its acquisition of Activision Blizzard Inc. [93] The FTC alleges that if the merger goes through, Microsoft would possess the sole ability to manipulate Activision prices, game experience on competing platforms, and withhold Activision content “from competitors entirely.” [94] In a view to a future where the issues of globalization and platform monopolies go hand in hand, it ends up being the case that the U.S., burdened with its current antitrust framework, will have to wait and take note of the manner in which the European Union and United Kingdom approach the regulation of platform monopolies. [95] Similarly, as discussed earlier with regard to the precedent set by Ohio v. American Express (2018), [96] the issue of privacy also comes up. The argument has been made by Neo-brandeisians, that antitrust enforcement against the exclusionary practices of the same digital platforms mentioned can, as a tool, serve the protection of privacy. [97] They argue that the monopolistic barriers posed by the platform monopolies of today impede competitors that are “pro-privacy” from competing. [98] Indeed protection against privacy violations, access to diverse essential services, and the integration of markets across borders poses a direct impact on the direction a population's political future takes.

Conclusion

There has been a rise in centralized private power, as the consequence of modern case law on the subject of antitrust laws; most will agree this poses a significant threat to the social and economic conditions necessary for the functioning of a democracy. The work, advocacy, and fight against concentrated economic power of Justice Louis Brandeis has served as a guide to the Neo-Brandeisian movement, which today seeks a broader and stronger enforcement of competition law. This movement, despite its noble intent, is not without its detractors and those who argue for the necessity of an antitrust enforcement focused solely towards the goal of economic efficiency and the protection of consumers. The history of antitrust legislation, however, makes it clear that the role of antitrust has always been the protection of democratic principles and of a population from the harms of concentrated economic power. The departure then, from strict economic considerations and the consumer welfare standard of the Neo-Brandeis movement is in line with this early anti-monopolistic movement. The Neo-Brandeis approach with its emphasis on social and political considerations presents a path forward, including for the complex contemporary issues presented above. The goals of protecting economic fairness, small business, and labor remain in line with the broader goals of safeguarding democracy and a people’s right to self determination against concentrated economic power.

Sources

Vile, John R., “Great American Judges: An Encyclopedia.” (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Inc., 2003). 122.

Ibid.

Muller v. Oregon, 208 U.S. 412 (1908).

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Finkelman, Paul, “Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present from the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-First Century.” Oxford University Press (2009).

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. 2018.

Hovenkamp, Herbert, “Antitrust and Platform Monopoly.” The Yale Law Journal Vol.130 (June 2021) 1952-2273.

Congressional Record. December 12, 1950 Vol. 96, Part 12 — Bound Edition. 81st Congress - 2nd Session.

Baker, Jonathan B., “Finding Common Ground Amongst Antitrust Reformers.” 84 Antitrust Law Journal No. 3 (2022).

Pitofsky, Robert. “The Political Content of Antitrust.” University of Penn Law Review. Vol.127. 1051-1075.

United States Congress. Senate. Sherman Antitrust Act. 26 Stat. 209. 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7. 51st Cong.

Pitofsky, Robert. “The Political Content of Antitrust.” University of Penn Law Review. Vol.127. 1051-1075

Baker ABA

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It.”Antitrust, Vol. 35, No. 3, (Summer 2021:) 33-4

Crane, Daniel. “On antitrust and big tech, Biden must return to his centrist roots.” The Hill. April 13, 2021.

Bork, Robert H. and Bowman Jr., Ward S., “The Crisis in Antitrust.” Columbia Law Review Vol. 65, No. 3 (March 1965), 363-376.

Ibid.

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It.”Antitrust, Vol. 35, No. 3, (Summer 2021:) 33-45.

Crane, Daniel. “On antitrust and big tech, Biden must return to his centrist roots.” The Hill. April 13, 2021.

Ibid.

Carl Shapiro. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and how to Fix it,” Antitrust, Vol. 35 No.3 Summer 2021., 33

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. 2018.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Brandeis, Louis. 1911.

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. 2018.

Ibid.

“The Sherman Antitrust Act.” 26 Stat. 209, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1 – 7. (1890).

“The Clayton Antitrust Act” 15 U.S.C. 12-27. (1914)

“The Federal Trade Commission Act” 15 U.S.C. §§ 41-58 (1914).

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Ibid.

“The Celler-Kefauver Act” P.L. 81-899 (1950).

United States Congressional Record. 1950. No. 16,452.

McCloskey, Deirdre and DeMartino, George, “The Oxford Handbook of Professional Economic Ethics” Oxford University Press. 2016.

Ibid.

Bunting v. Oregon. 243 US 426 (1917).

Lochner v. New York. 198 US 45 (1905).

Bunting v. Oregon. 243 US 426 (1917).

McCloskey, Deirdre and DeMartino, George, “The Oxford Handbook of Professional Economic Ethics” Oxford University Press. 2016.

United States v. E.C. Knight Co. 156 US 1 (1895).

Ibid.

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. 2018.

Ibid.

United States v. Columbia Steel. Co. 334 U.S. 495 (1948).

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix it,” Antitrust, Vol. 35 No.3 Summer 2021., 33.

Ibid.

Morrison v. Murray Biscuit Co., 797 F.2d 1430 (1986).

Ibid.

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko. 540 U.S. 398, 407 (2004).

Ibid.

Totenberg, Nina. “Justice Antonin Scalia, Known For Biting Dissents, Dies At 79.” NPR. February 13, 2016.

Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko. 540 U.S. 398, 407 (2004).

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Verizon Communications Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko. 540 U.S. 398, 407 (2004).

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. 2018.

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Pitofsky, Robert. “The Political Content of Antitrust.” University of Penn Law Review. Vol.127. 1051-1075.

Baker, Jonathan B. “Finding Common Ground Among Antitrust Reformers.” Antitrust Law Journal No. 3. Vol. 84. 705-751. (2022).

Weinstock, Lida R. “Introduction to U.S. Economy: Productivity.” Congressional Research Service. January 3, 2023.

Ibid.

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and how to Fix it,” Antitrust, Vol. 35 No.3 Summer 2021., 33.

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

Bolton et. al, “Predatory Pricing: Strategic Theory and Legal Policy.” Justice.gov.

Khan, Lina M. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” Yale Law Journal. Vol. 126. No. 3. (2017).

Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993).

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

United States v. Vulte, 233 U.S. 509 (1914).

Brooke Group Ltd. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 509 U.S. 209 (1993).

Ibid.

Hemphill, Scott C. and Weiser, Phillip J., “Beyond Brooke Group: Bringing Reality to the Law of Predatory Pricing.” Yale Law Journal. Vol. 127, No. 7. (2018).

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ohio v. American Express Co. 585 US _ (2018).

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

Ohio v. American Express Co. 585 US _ (2018).

Ibid.

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

Ibid.

Baker, Jonathan B. “Finding Common Ground Among Antitrust Reformers.” Antitrust Law Journal No. 3. Vol. 84. 705-751. (2022).

Ibid.

Ohio v. American Express Co. 585 US _ (2018).

Khan, Lina M. “The Ideological Roots of America’s Market Power Problem.” 127 Yale L. J. F. 960 (2018).

Ohio v. American Express Co. 585 US _ (2018).

Baker, Jonathan B. “Finding Common Ground Among Antitrust Reformers.” Antitrust Law Journal No. 3. Vol. 84. 705-751. (2022).

Wu, Tim. “The Curse of Bigness Antitrust in the New Gilded Age.” Columbia Global Reports. (2018).

Evenett et. al. “Antitrust Policy in an Evolving Global Marketplace.” Brookings. 1-27. (2004).

Ibid.

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

Ibid.

“FTC Seeks to Block Microsoft Corp.’s Acquisition of Activision Blizzard, Inc.” Federal Trade Commission. (December 8, 2022).

Ibid.

Shapiro, Carl. “Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix it,” Antitrust, Vol. 35 No.3 Summer 2021., 33.

Ohio v. American Express Co. 585 US _ (2018)

Hubbard, Sally. “Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition Online.” Testimony before the 115th Congress: House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law (2020).

Ibid.