Monkey-ing Around: How One Monkey Shaped Copyright Law for Artificial Intelligence

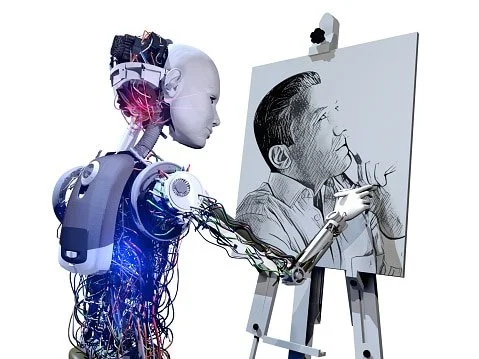

“Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transcended its traditional role as a mere problem-solving tool, as it now produces stunning artworks, insightful essays, and soul-stirring music that rival those created by human beings.” The previous sentence was generated by an artificial intelligence bot, ChatGPT. Artificial intelligence has been top of mind since the rise of AI bots like ChatGPT. It has previously been used to screen job applications and make video recommendations on sites like YouTube, but now, AI can generate essays, art, music, and more with a simple prompt, bringing up questions over ownership rights. What is the legal future of AI? Can AI have intellectual property rights over the art it creates? Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they used AI to create?

April 2023 | Annie Vong (Editor-in-Chief)

“Artificial Intelligence (AI) has transcended its traditional role as a mere problem-solving tool, as it now produces stunning artworks, insightful essays, and soul-stirring music that rival those created by human beings.” [1] The previous sentence was generated by an artificial intelligence bot, ChatGPT. Artificial intelligence has been top of mind since the rise of AI bots like ChatGPT. It has previously been used to screen job applications and make video recommendations on sites like YouTube, but now, AI can generate essays, art, music, and more with a simple prompt, bringing up questions over ownership rights. What is the legal future of AI? Can AI have intellectual property rights over the art it creates? Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they used AI to create?

Firstly, to define intellectual property (IP), it gives ownership to creative works and processes and has three main types: copyright, trademark, and patents. Copyright law started with The Copyright Act of 1976, [2] which gave IP rights to artistic, literary, or intellectually-created works. Copyright differs from patents – which gives IP rights to technical inventions – and trademark – which gives IP rights to words, phrases, or designs. [3] Regarding copyright, the U.S. is one of many countries to adopt copyright law with the Berne Convention, which states that as a work of art is written, documented, or recorded physically, the creator of that work has automatic copyright, meaning that creators do not need to file any official forms to have copyright. [4]

Part One: Can Artificial Intelligence have Copyright?

The precedent for whether AI can have copyright emerges from Naruto v. David Slater et al, a case involving a monkey taking a selfie in Sulawesi, Indonesia. [5] Wildlife photographer, David Slater, left his camera unattended near the black macaque exhibit and a monkey named ‘Naruto’ took a selfie with his camera. Slater later published these photos in a photobook, claiming copyright only for himself. [6] People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), an animal rights organization, [7] sued on Naruto’s behalf for copyright infringement, arguing that because the monkey took the selfie by itself, Naruto is the creator of the work; therefore, Naruto has copyright due to the terms from the Berne Convention. [8] (Using the courts to secure rights for animals is not new; the courts have been used in an attempt to secure bodily autonomy rights for an elephant in the Bronx Zoo.)[9] Additionally, the Copyright Act defines five rights that copyright holders have, but does not explicitly define what authorship entails. PETA argued that the term “authorship” in the Copyright Act is up to interpretation. [10] For PETA, expansion of copyright ownership to animals can set precedent for animals to have other rights as well. And so, the courts had to decide the following issue at hand: Who owns copyright? Can a non-human creator own copyright?

The defendant, Slater, argued that he owned the camera equipment and that he created the situation that resulted in the picture being taken. For example, he checked the angle of the shot, set up the equipment, adjusted exposure, etc. He also argued that he has standing whereas Naruto did not. Who the court decides to give copyright to significantly impacts Slater's photography business, however, Naruto is not financially impacted at all if copyright is granted or not. The court ruled against PETA and Naruto citing their lack of standing. The district court reasoned that because the Copyright Act does not extend copyright to animals explicitly, the law does not apply to Naruto and that both PETA and Naruto were legal strangers to the case. [11] If a human were to file a copyright infringement suit on behalf of AI, that suit would likely also be dismissed as well on the same grounds. However, unlike Naruto, if AI were to ever represent itself in court, the court may find that it is not a legal stranger to the case and has standing.

After PETA and Naruto’s loss at the district court level, PETA appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which affirmed the district court’s decision and emphasized that PETA and Naruto did not have standing to file for copyright infringement. They interpreted that the authorship under the Copyright Act specifically referred to “persons” or “human beings” and that Naruto did not fit under either category. [12]

The emphasis on “persons'' holding copyright brings up the philosophical question of what counts as a “person.” Must a person have consciousness? Intelligence? Must a person be of the human race? At what point can AI cross that threshold into being considered a person? Legally, the courts have extended the definition of “persons'' to include non-human entities before. For example, in common law, courts have ruled that the Catholic Church has the right to sell property. [13] Furthermore, in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby (2014), the Supreme Court has granted corporations personhood and ruled that they can refuse to follow a federal healthcare mandate covering birth control if that mandate violated their religious exercises. [14] And, in Citizens United v. FEC (2012), the Supreme Court ruled that corporations have the right to freedom of speech via campaign contributions. [15] However, it can be argued that these groups (the Catholic Church, Hobby Lobby, and Citizens United) are collections of human members, and that AI is not, making them more different than similar to these groups that have gained rights through the courts. As rights for corporations have expanded, one question remains unexplored — can corporations who use AI as a tool to generate works of art have copyright? Can humans who use AI as a tool to make music have copyright?

Part Two: Can humans who use AI as a tool have copyright over the art they create?

In April, a social media user named, “Ghostwriter977” posted a song that claimed to be crafted using AI. [16] The song, “Heart on My Sleeve,” used the likeness of two pop stars, Drake and The Weeknd. Universal Music Group (UMG), a corporation that owns the music label that Drake and The Weeknd have signed under, have filed a copyright claim taking down all posts containing this song. [17] UMG put out a response, “the training of generative AI using our artists’ music represents both a breach of our agreements and a violation of copyright law.” [18] Does UMG have grounds to copyright this song, even though it was not produced by Drake and The Weeknd themselves? To understand this, consider a scenario where AI was not used at all. Under the Copyright Act, use of copyright material is permitted in some cases such as in training, education, commentary, parody, etc. [19] If it is used (for example, if it is used in a parody or commentary) there must be some modification, transformation, or addition to the copyrighted material in order for it to constitute as fair use. It cannot be an exact copy of the material.

There exists an argument that Ghostwriter977 did not use any existing copyright material (or any other published songs) in the song itself, so it constitutes as a fair use of copyrighted material. But, on the other hand, there also exists an argument that Ghostwriter977 was using published songs (copyrighted material) to train the AI and used Drake and The Weeknd’s likeness to make a profit from the song. It can be argued that even if Ghostwriter977 used copyrighted material to train the AI, the song is transformative enough to count as fair use. It is still unknown whether courts will accept the argument that using AI as a tool in creating works of art is enough for the human creator to have copyright.

All of these cases pertaining to AI and intellectual property rights pose giant questions in copyright law. Drawing from Naruto, courts would most likely decide against artificial intelligence having copyright, but issues with copyright and AI move faster than the creation of legislation, and courts are forced to interpret law where law doesn’t exist, which can lead to a vulnerability in copyright law where it only takes one case to change the future of copyright for non-human entities forever.

Sources

“Introducing ChatGPT.” OpenAI

United States Congress. The Copyright Act of 1976. 94th Congress, Introduced

in Senate 15 January 1975. Pub. L. 94–553

“Trademark, patent, or copyright.” United States Patent and Trademark Office

“Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works” World Intellectual Property

Organization

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

O’Donell, Nicholas. “Is the ‘monkey selfie’ case making a monkey out of the law?”Apollo

Magazine. July 28, 2018

“About PETA: Mission Statement.” PETA

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

Lissett, Jenifer. “The Legal Rights of the Elephant in the Room.” UNLV Undergraduate Law

Review. February 2022

“UPDATE: ‘Monkey Selfie’ Case Brings Animal Rights Into Focus.” PETA, January 6, 2016

Naruto v. Slater, No. 16-15469 (9th Cir. 2018)

Ibid.

Totenberg, Nina. “When Did Companies Become People? Excavating The Legal Evolution.”

National Public Radio. July 28, 2014

Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, 573 U.S. 682 (2014)

Citizens United v. Federal Elections Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

Pahwa, Nitish. “How Two Music Legends Found Themselves at Some Anonymous TikTokker’s

Mercy.” Slate. April 17, 2023

Ibid.

Ibid.

“U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index.” U.S. Copyright Office. February, 2023

Bankruptcy Uncoded: The Biden Administration's New Changes

Student loans are a staple of higher education in this era. 43.5 million borrowers alone have federal student loan debt. The amount of student loan debt in 2022 was $1,757,200,000,000, and the average amount of student loan debt is $37,574 per student borrower. Furthermore, the average public university student will take out a whopping $31,410 to obtain their bachelor's degree. All of these numbers reveal the massive amount of debt that students in the United States incur to attend school. Many of them will not go into million-dollar careers, leaving them to spend their adult lives paying off student loans. Given the enormity of this issue, borrowers push for federal student loan forgiveness programs—but most of the laws do not come off the ground…

February 2023 | Jenifer Lissett (Staff Writer and Editor)

I. Introduction

Student loans are a staple of higher education in this era. 43.5 million borrowers alone have federal student loan debt. [1] The amount of student loan debt in 2022 was $1,757,200,000,000, and the average amount of student loan debt is $37,574 per student borrower. [2] Furthermore, the average public university student will take out a whopping $31,410 to obtain their bachelor's degree. [3] All of these numbers reveal the massive amount of debt that students in the United States incur to attend school. Many of them will not go into million-dollar careers, leaving them to spend their adult lives paying off student loans. Given the enormity of this issue, borrowers push for federal student loan forgiveness programs—but most of the laws do not come off the ground. This article will explore one new avenue for borrowers to discharge their student loans via bankruptcy. Section II will define the basics of the U.S. bankruptcy code. Then, Section III will shift to defining the previous standard before the Biden Administration changed their guidelines of federal student loans and bankruptcy. Finally, Section IV will detail the Biden Administration’s guideline changes to bankruptcy and federal student loans.

II. What is a debt and how does bankruptcy get rid of it?

According to 11 U.S. Code § 10—the set of U.S. laws that govern bankruptcy proceedings—a debt is a “liability on a claim.” [4] To further clarify, a liability is used in a context where there is a risk in entering into a contract. For example, a creditor, or someone who loans a consumer money, enters into a contract where they face a loss if the consumer does not pay back the debt. [5] Although, a debt is more inclusive than this and can involve a consumer owing money to a friend or family member. A contract is not a required feature to owe someone a debt.

These types of debts are considered consumer debts, or, in other words, these are not associated with businesses. Everyday people take out loans, charge purchases to their credit card, or borrow money from an acquaintance. If people become incapable of paying these debts, consumers can file for Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcy to discharge, or end their liability, in order to pay the debt back to the creditors. [6] Moreover, if a consumer cannot pay these debts back, it is fairly easy within the bankruptcy code to discharge them.

A consumer also has to pay attention to the distinction between an unsecured debt and a secured debt. Most consumer debts listed above fall under the unsecured loan bracket, as these debts do not have any physical property attached to them. [7] For example, a car loan or mortgage is a loan that is secured because there is physical property attached to the loan. The bank or lender has ownership of the property until it is paid off. On the other hand, credit card debt or payday loans are unsecured because there is no property attached to the loan. In those cases, a bank lent money to a consumer under the knowledge that it would be a standard loan with the expectation that it would be paid back. [8]

III. Student Loans and How it Differs.

Student loans in bankruptcy are more complex to discharge than regular unsecured consumer debts. Consumers have to go through a tedious system to try and meet a difficult standard of “undue hardship.” Undue hardship is an ambiguous standard that does not have a set definition. [9] One consumer can meet the standard by having constant medical debt; however, in a different district, another consumer who is in a similar situation may not meet this standard. In some states, it is up to consumers to prove a “certainty of hopelessness,” which is an extra burden in addition to proving undue hardship. [10] As a result of this vague standard, most student loans are not discharged in bankruptcy.

Previously, when a consumer wanted to discharge a student loan in bankruptcy, they would have needed to initiate an adversary proceeding against the student loan provider. [11] An adversary proceeding is, essentially, a lawsuit tried in bankruptcy court. [12] A consumer sues their student loan provider and fights their student loan at the adversary proceeding. [13] This process is costly to the consumer, though, as they will have to hire private attorneys to represent them. Consumers also have to fight against the seemingly endless onslaught of paperwork from the student loan provider’s legal team.

Conti v. Arrowood Indemnity Co. (2020) proves that the "undue hardship” student loan standard was an acceptable standard that the higher courts were not willing to change. In Conti v. Arrowood Indemnity Co., (2020) the plaintiff listed her private student loans in her bankruptcy and initiated an adversary proceeding to show that these student loans did not meet the student loan definition of bankruptcy. [14] The plaintiff tried to limit what could be considered a student loan, but by deciding to not hear the case, the Supreme Court of the United States asserted that the current student loan definition in bankruptcy and their dischargeability is acceptable. [15]

That said, consumers have another way of getting rid of their student loans without starting an adversary proceeding against their student loan providers, but it is very narrow in its application. Federal student loans can be discharged if they meet any one of the following conditions: (1) a student takes out a federal student loan to attend an unaccredited program or university, or (2) a student took out a student loan that surpasses the cost of attendance. If a consumer meets any of these conditions, then they, if included in their bankruptcy petition, can have these loans discharged. However, this is not always the case. Many student loan providers take advantage of the stringent undue hardship standard and do not file a claim with bankruptcy courts, meaning consumers assume they still owe the debt because it was not dischargeable. Consumers will continue making payments and student loan providers will continue collecting. This is all due to the ambiguous nature of the undue hardship standard. There are current cases, such as Fennell, v. Navient Sols. (2022), trying to fight against this abuse from student loan lenders. [16]

IV. Biden Administration’s Changes to Bankruptcy and Federal Student Loans

The Biden Administration, in their plight to ease the burden of student loans, loosened the undue hardship standard that consumers with federal student loans had to meet. The Biden Administration, along with the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Department of Education (DOE), will not oppose adversary proceedings that are dealing with discharging student loans. The DOE and their attorneys will review a plaintiff’s case information, “apply the factors courts consider relevant to the undue-hardship inquiry,” and determine whether to allow the adversary proceeding to be unopposed. [17] In other words, consumers who file an adversary proceeding against federal student loan providers can discharge their loan without having to go through the entire adversary process. [18] The DOE, after reviewing a consumer's claim, will simply not file a motion of opposition to the adversary proceeding. [19]

The Biden Administration’s changes make the process of discharging federal student loans much easier and less burdensome to consumers who are already facing other financial hardships. Consumers will not have to accrue more debt, especially in the form of attorneys fees, while trying to get rid of their debt. [20] Also, consumers, when filing for bankruptcy, can rid themselves of all their debt rather than have to keep their substantial student loan debt. In all, this is a step in the right direction for consumers to rid themselves of all debts.

V. Conclusion

The Biden Administration, the DOJ, and the DOE have all taken a step in the right direction for student loan forgiveness. Though they made it easier for consumers to get rid of federal student loan debt, there is still more that needs to be done. Consumers who have to file for bankruptcy solely to discharge their student loans must incur a financial burden for 7 to 10 years. Credit reporting agencies (CRAs) have the right to report bankruptcies for a minimum of 7 years and up to 10 years after the date of filing, meaning any potential creditors can deny credit for up to 10 years after bankruptcy. [21] This is a harsh price consumers have to pay to try and get rid of their federal student loans.

Not only do consumers have to deal with the negative impact of a bankruptcy on their credit report, but they must also deal with any derogatory reporting from other debts that were included in their bankruptcy. [22] Creditors can choose to report inaccurate past-due payments, balances, or statuses which, without intervention, can further affect a consumer's credit history and score. So, consumers—after going through bankruptcy—will still have to deal with the possible incorrect reporting and, without knowledge of the Federal Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), consumers may unintentionally leave it alone until the credit account and its history is removed from the credit report.

As if the negative credit impacts that a consumer faces after filing for bankruptcy were not bad enough, this change to the bankruptcy code only covers federal student loans. Just as many students take out private student loans as they do federal student loans. Students may not qualify for federal student loans, leaving them no access to discharge private student loans. This means that there are still consumers out there who have to continue to pay for their student loans just because they may have had eligibility issues in obtaining federal student loans. This highlights inequity in student loan forgiveness policies that needs to be addressed.

Without intervention from Congress, consumers can expect inconsistencies in federal student loan forgiveness as policies change from one administration to the next. [23] To give consumers protection from policy-related instability, Congress must enact a law that stipulates what the DOE must do when adversary proceedings are brought against them in bankruptcy courts. Until then, consumers have no certainty in student loan forgiveness and must deal with fluctuating policy.

Sources

Hanson, Melanie. “Student Loan Debt Statistics,” Education Data Initiative, February 10, 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Bankruptcy 11 U.S. Code (2018), § 101.

Ibid.

“Bankruptcy Basics Glossary.” Bankruptcy Basics Glossary. United States Courts. Accessed March 4, 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Minskey, Adam. “Biden Administration Announces Huge Bankruptcy Changes for Student Loans,” Forbes, November 17 2022.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Conti v. Arrowood Indemnity Co., 612 B.R. 877 (6th Cir. 2020).

Ibid.

Fennell, v. Navient Sols., 2:22-cv-01013-CDS-NJK EMD.

Minskey, Adam. “Biden Administration Announces Huge Bankruptcy Changes for Student Loans,” Forbes, November 17 2022.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Bankruptcy and Your Credit Report.” Bankruptcy & Your Credit Report: Western District of Washington, February 18, 2023.

Ibid.

Minskey, Adam. “Biden Administration Announces Huge Bankruptcy Changes for Student Loans,” Forbes, November 17 2022.

Telling the Whole Truth and Nothing but the Truth about Courtroom Intimidation

In United States v. Edgar Ray Killen (2007), Edgar Killen, a former Ku Klux Klan leader, was charged with the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964. One of the witnesses in the case, Louis Allen, was brutally murdered before he could testify in trial. Killen was eventually convicted of three counts of manslaughter in 2005. In Justice Dickinson’s opinion, he wrote, “The Klan's official policy, which was openly discussed at Klan meetings, was to use whatever force necessary — including harassment, intimidation, physical abuse, and even murder — to maintain racial and social segregation in Mississippi.” This case is a tragic example of the lengths some individuals or groups are willing to go to in order to silence witnesses and maintain their power and control. Cases such as United States v. Edgar Ray Killen (2007) serve as a reminder of the challenges and risks involved in seeking justice. This case is crucial to the government because it highlighted the very serious consequences of witness intimidation. It also demonstrated the government's commitment to pursuing and prosecuting organized crime and set a precedent for the government's handling of similar cases…

February 2023 | Allison Hardy (Staff Writer and Editor)

In United States v. Edgar Ray Killen (2007), Edgar Killen, a former Ku Klux Klan leader, was charged with the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964. One of the witnesses in the case, Louis Allen, was brutally murdered before he could testify in trial. Killen was eventually convicted of three counts of manslaughter in 2005. In Justice Dickinson’s opinion, he wrote, “The Klan's official policy, which was openly discussed at Klan meetings, was to use whatever force necessary — including harassment, intimidation, physical abuse, and even murder — to maintain racial and social segregation in Mississippi.” [1] This case is a tragic example of the lengths some individuals or groups are willing to go to in order to silence witnesses and maintain their power and control. Cases such as United States v. Edgar Ray Killen (2007) serve as a reminder of the challenges and risks involved in seeking justice. This case is crucial to the government because it highlighted the very serious consequences of witness intimidation. It also demonstrated the government's commitment to pursuing and prosecuting organized crime and set a precedent for the government's handling of similar cases.

18 U.S. Code § 1512 constitutes a broad prohibition against tampering with a witness, victim, or informant in Federal proceedings. [2] It applies to proceedings before Congress, executive departments, and administrative agencies, as well as civil and criminal judicial proceedings. The penalties for violating 18 U.S. Code § 1512 can be substantial, including fines and imprisonment for up to 20 years, depending on the specific circumstances of the offense. [3] The effectiveness of these penalties depend on their consistent enforcement and application in every case.

Witness intimidation is but one aspect of a larger set of problems related to protecting crime victims and witnesses from further harm. Related crimes include domestic violence, acquaintance rape, stalking, exploitation of trafficked women, gun violence, gang-related crime, bullying in schools, drug trafficking and organized crime. [4] To prove that the lack of witness protection is directly affecting justice, in 2021, only about 45.6 percent of violent crimes were reported to police. Furthermore, small-scale studies and surveys of police and prosecutors suggest that witness intimidation is not only highly pervasive, but rapidly increasing. For example, a study of witnesses appearing in criminal courts in Bronx County, New York revealed that 36 percent of witnesses had been directly threatened. [5] Among those who had not been threatened directly, 57 percent feared reprisals. [6] According to the NYU Dispatch, detectives often made “minimal to no effort to locate, identify, interrogate, or investigate suspects,” leading victims to believe the effort and trauma involved in reporting a rape would all eventuate to nothing due to the “lax approach” of police officers, [7] which is the exact reason so many crimes remain unreported.

To this day, witnesses and victims in many communities are still deprived of the opportunity to testify the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. That said, the U.S. government has policies in place that claim to protect victims and key witnesses from being subjected to intimidation in and out of the courtroom. These policies include witness protection programs, restraining orders, and other measures designed to ensure the safety and security of witnesses to prevent them from being subjected to retaliation or intimidation. In some cases, witnesses may be placed in witness protection programs, where they are relocated to a different location and given a new identity to keep them safe. Additionally, the court can also order a restraining order against the individual who is intimidating the witness. In extreme cases, law enforcement officers may provide 24-hour protection to high-risk witnesses. What other options are available to witnesses experiencing courtroom intimidation?

Victims can contact the police, reach out to a support group, report the retaliation to the court, gain a restraining order, and/or cooperate with the prosecution to build a case against the person who is intimidating them. Speaking up about intimidation can be a difficult process, but it is important for victims to know that they have the right to protection and that there are people and resources available to help keep them safe. Additionally, it is crucial for victims and witnesses to understand that their cooperation within the criminal justice system can play a vital role in holding their perpetrators accountable and stopping further crimes from being committed. Specific measures taken to protect a victim or witness depend on the individual circumstances of each case, but should there be more drastic consequences to deter criminals from undermining the justice system?

Courts should be working with victims from the beginning of a case to inform and ensure their protection in exchange for their full cooperation, such as informing the court of any injustices. Many victims do not know or think they can speak up when someone threatens them. If the court informs victims of their right to speak freely if they experience courtroom intimidation, it will establish a sense of trust. Although there should be a higher penalty in place to deter ruthless criminals from sabotaging the justice system, the government has many protections available to witnesses and victims to uphold the integrity of the court. Hopefully, the government will soon recognize that if over half of violent crimes in this country are going unreported that it will only lead to even more injustice in the American justice system.

Sources

Dickinson, Justice. “Killen v. State.” Legal research tools from Casetext, June 28, 2007.

“1729. Protection of Government Processes -- Tampering with Victims, Witnesses, or Informants -- 18 U.S.C. 1512.” The United States Department of Justice, January 17, 2020.

Ibid.

“Witness Intimidation.” ASU Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, December 1, 2022.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Dispatch. “Why Do So Many Crimes Go by Unreported in the States?” The NYU Dispatch, 31 Aug. 2018,

Is Discrimination Generally Applicable?

One of the most popular amendments in the U.S. Constitution is the First Amendment. The high recognition of this amendment comes from the many claims of authority figures and governing bodies violating people's First Amendment rights, some more often than others. One of the provisions within the First Amendment is the Free Exercise Clause. This clause states that the practice and expression of opinion related to religion are protected under the First Amendment. It “protects citizens' right to practice their religion as they please, so long as the practice does not run afoul of "public morals" or a "compelling" governmental interest”— two vague standards. Moreover, not only does this amendment protect the freedom to practice religion and express an opinion, but it also allows the exemption from some generally applicable laws, as long as the violation is for religious reasons…

February 2023 | Jesse Fager (Communications Director) and Kira Kramer (Staff Writer and Editor)

One of the most popular amendments in the U.S. Constitution is the First Amendment. The high recognition of this amendment comes from the many claims of authority figures and governing bodies violating people's First Amendment rights, some more often than others. One of the provisions within the First Amendment is the Free Exercise Clause. This clause states that the practice and expression of opinion related to religion are protected under the First Amendment. It “protects citizens' right to practice their religion as they please, so long as the practice does not run afoul of "public morals" or a "compelling" governmental interest”— two vague standards. [1] Moreover, not only does this amendment protect the freedom to practice religion and express an opinion, but it also allows the exemption from some generally applicable laws, as long as the violation is for religious reasons.

Violations of the Free Exercise clause are evaluated by analyzing if the laws or conditions being violated are neutral and generally applicable. The landmark case, Employment Division v. Smith (1990) has set the precedent for cases involving generally applicable laws. In this case, “Alfred Smith and Galen Black were fired from their jobs as private drug rehabilitation counselors for ingesting peyote as part of a sacrament of the Native American Church.” [2] When they applied for unemployment benefits, “the Employment Division denied their request because they had violated a state criminal statute.” [3] Alfred Smith filed suit against the Employment Division and won his case in the lower courts. However, the Supreme Court reversed the decision, holding that Smith’s and Black’s free exercise rights were not violated and that the denial of benefits did not violate the First Amendment. Smith held that where “prohibiting or burdening the free exercise of religion is not the object [of a law] but merely the incidental effect of a generally applicable and otherwise valid provision, the First Amendment has not been offended.” [4] A law is generally applicable if there are no exceptions or built-in opportunities for the government to target people on the basis of their religion. Conversely, “a law is not generally applicable if it invites the government to consider the particular reasons for a person’s conduct by creating a mechanism for individualized exemptions.” [5] In 2021, a Supreme Court case utilized the Employment Division v. Smith (1990) case and its definitions of neutral and generally applicable laws to rule on a court case regarding the violation of the Free Exercise clause of the First Amendment.

In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia (2021), Pennsylvania Catholic Social Services (CSS) filed suit against the City of Philadelphia for violation of the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment, particularly those protecting religious liberty. In 2018, attention was drawn to CSS’s refusal to certify unmarried and same-sex couples as it would violate their religious ideology. The City proposed an ultimatum that unless CSS agreed to certify same-sex couples, the City would no longer refer children to that agency or enter into a contract with them in the future. The City made this decision on the grounds that CSS’s refusal to certify same-sex couples violated a non-discrimination provision in the agency’s contract as well as the City’s non-discrimination requirements stated in their Fair Practices Ordinance. As a result of the referral freeze issued by the City, CSS sought to enjoin the referral freeze on the basis that it violated their First Amendment rights.

After the referral freeze issued by the City of Philadelphia, Catholic Social Services decided to sue the city for violating its First Amendment right under the Free Exercise Clause. After CSS lost in two lower courts, the Supreme Court sided with CSS in a unanimous decision. The justification for this decision was because of the influence of “generally applicable.” In this case, the City’s action of providing an ultimatum—allowing same-sex couples or else the contract will be discontinued—burdened CSS’s religious exercise. If CSS wanted to continue operating with the City, they would have to violate their religious beliefs. This type of burdening on religion is not considered neutral and generally applicable, which means that it was subject to strict scrutiny. Strict scrutiny is used in two different kinds of cases: fundamental rights cases and suspect classification cases. The former deals with constitutional issues and the latter deals with discrimination against marginalized groups. Fulton is a fundamental rights case because the constitutionality of religious exercise is in question. Strict scrutiny is the highest level of judicial review, in which a law is presumed to be unconstitutional and the burden of proof falls on the government to prove that the law is constitutional. In order to prove this, the end goal of the law presented must be compelling, and the law itself must be narrowly tailored toward achieving that compelling goal. [6]

In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia (2021), the federal government was accused of violating the First Amendment because the discrimination policies maintained within the contract between their organization and CSS were decided as not generally applicable. In order to understand the court’s ruling on the case, it is imperative that neutral and general applicable laws be defined; in this case, “neutrality and general applicability are requirements for the validity of laws under the Free Exercise Clause because there is no legitimate state interest that justifies violating them.” [7] There is no law that legitimately holds the object of restricting religion. Laws are designed to address specific incidents where harm is caused by religion, but these incidents are not likely to be unique to religion; therefore, “a classification limited to religion carries on its face the indicia of illegitimate purpose.” [8] Essentially, cases that pursue the persecution of religion itself are illegitimate, but where specific harm is caused by religion the law can intervene.

Another important aspect is that the parties involved in this case were a government organization and a religious foster care agency. Free Exercise Clause cases almost always involve government employers. The First Amendment protects private-sector employers from government interference. In Philadelphia, there exist multiple public and private agencies that recruit and train foster parents, along with facilitating placements. There are a few differences between state-run facilities and private agencies. Every state has its own child welfare office, and those state agencies have the authority to license foster/adoptive parents and issue them certificates. Custody of all children within the foster care system falls to the state because private agencies are considered to be private businesses. Private agencies, however, must be approved and on record with the Secretary of State to ensure that they are conducting foster care and adoption services.When an agency requests approval, “the state then reviews the private agency’s request and determines whether it will approve the private agency for foster care only or for both foster care and adoption.” [9] Families can choose to work with either public or private entities when deciding to foster.

Child welfare policies and procedures are run by the state; therefore, not all states allow the operation of private organizations. Some only allow state agencies to facilitate training and placement while others create contractual agreements between private foster care and adoption agencies. The City of Philadelphia contracts with multiple private agencies to recruit and train foster parents, including CSS. Philadelphia can create annual contracts with stipulations and exemptions that the private agency they are looking to contract with must agree to. However, it is difficult to craft contracts with extreme exemptions when balancing multiple interests.

Interestingly enough, in Fulton v. Philadelphia (2021), there was one majority opinion and two concurring opinions. The majority opinion—written by Chief Justice Roberts and joined by Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Barrett—argued that the City of Philadelphia violated Catholic Social Services’ First Amendment right because it gave CSS an ultimatum: either be cut off from the City’s partnership or curtail its mission to allow same-sex marriage couples to foster children. Chief Justice Roberts also stated that this case falls outside of the standards set in Employment Division v. Smith, (1990) because the laws that the city is burdening CSS with are not “generally applicable.” While Chief Justice Roberts stated that there was no reason to challenge Smith, Justice Barrett wrote a concurring opinion stating that the arguments against Smith are compelling. She argued that strict scrutiny is not satisfied in this case as there is no compelling end goal for Philadelphia to freeze its contract with Catholic Social Services. [10] Barrett ended up joining the majority regarding the overturning of Smith, stating that “there would be a number of issues to work through if Smith were overruled.” [11] Justices Kavanaugh and Breyer joined in Barrett's concurring opinion. Justice Alito gave another concurring opinion, in which Justices Thomas and Gorsuch joined. Justice Alito concurred, stating that he would overrule Smith and reverse the decision because Philadelphia violated the Free Exercise Clause; therefore, CSS is entitled to an injunction barring Philadelphia from taking such action. [12]

The role of the courts is to examine laws affecting religious exercise to determine if they are generally applicable and whether the object of the law is neutral. Understanding neutral and generally applicable laws is integral to interpreting the Court’s ruling on this case, previous cases, and those to come. While the LGBTQ+ community is still struggling to have the same rights and privileges afforded to heterosexual couples, the Court’s ruling did not examine this issue in terms of whether or not LGBTQ+ persons ought to foster. Their ruling came as a result of analyzing the contractual relationship between the City and CSS. The City was required to reinstate its contract with CSS and exempt CSS from Philadelphia’s nondiscrimination ordinance. This decision actually maintains LGBTQ+ rights, as it did not rule on the issue of whether or not same-sex couples ought to be able to foster through a Catholic agency. The Court managed to “sidestep addressing Smith by holding that the law prohibiting discrimination against married LGBTQ couples was not a generally applicable law because it allows for some discretion in selecting foster parents.” [13] Ultimately, this Supreme Court case still leaves the question of how the Court will deal with cases that do fall into Smith up to interpretation.

Sources

“First Amendment and Religion.” United States Courts. Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. Accessed February 25, 2023.

Hermann, John R. Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith. The First Amendment Encyclopedia, 2009.

Ibid.

“Fulton v. City of Philadelphia.” Constitutional Accountability Center, June 25, 2021.

Supreme Court of the United States. “Fulton et al. v. City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, et al.” 593 U.S. __ (2021).

“Strict Scrutiny.” Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Accessed February 25, 2023.

Bogen, David S. “Generally Applicable Laws and the First Amendment.” DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, 1997.

Ibid.

Hetro, Natalie. “Understanding the Differences between State and Private Foster Care Agencies.” Focus on the Family, May 9, 2022.

Supreme Court of the United States. “Fulton et al. v. City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, et al.” 593 U.S. __ (2021).

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Fulton v. City of Philadelphia.” Constitutional Accountability Center, June 25, 2021.

Crypto Catastrophe: After Exchange Giant FTX’s Collapse, What Comes Next?

During Super Bowl 56, a commercial aired showing comedian Larry David traveling through time while criticizing inventions that would become successful—such as the wheel and the light bulb. The commercial ended in the present day with David responding, “eh, I don’t think so,” to the suggestion that one cryptocurrency exchange company, Futures Exchange (FTX), was a safe and easy way to get into cryptocurrency. Ironically, David’s prediction proved to be correct. FTX, one of the leading cryptocurrency exchanges, filed for bankruptcy in November 2022, a stunning downfall of what was once a shining star in the industry. A month later, its founder and CEO, Sam Bankman-Fried, was arrested under several fraud charges. Bankman-Fried is currently awaiting trial, and deliberation is underway in bankruptcy court to attempt to recover lost assets. Additionally, government agencies are debating the future of cryptocurrency regulation. The legal outcomes of FTX’s collapse may dictate the livelihood of many impacted customers, as well as the future of financial laws in the United States…

February 2023 | Luke Perea (Staff Writer and Editor)

During Super Bowl 56, a commercial aired showing comedian Larry David traveling through time while criticizing inventions that would become successful—such as the wheel and the light bulb. The commercial ended in the present day with David responding, “eh, I don’t think so,” to the suggestion that one cryptocurrency exchange company, Futures Exchange (FTX), was a safe and easy way to get into cryptocurrency. Ironically, David’s prediction proved to be correct. FTX, one of the leading cryptocurrency exchanges, filed for bankruptcy in November 2022, a stunning downfall of what was once a shining star in the industry. A month later, its founder and CEO, Sam Bankman-Fried, was arrested under several fraud charges. Bankman-Fried is currently awaiting trial, and deliberation is underway in bankruptcy court to attempt to recover lost assets. Additionally, government agencies are debating the future of cryptocurrency regulation. The legal outcomes of FTX’s collapse may dictate the livelihood of many impacted customers, as well as the future of financial laws in the U.S.

Cryptocurrencies are a relatively new form of monetary units and their basic tenets are central to understanding why FTX failed. Despite the extensive cryptography used in its mining process, cryptocurrency—or crypto—in its simplest form is a digital currency with the intended purpose of acting as any currency does, representing monetary value and being a medium for transactions. [1] However, most crypto today resembles traditional assets such as stocks and commodities, as their value comes purely from supply and demand. Unlike fiat money—money that is managed by a central national bank—crypto is decentralized. [2] Instead of being managed by a third party, trading and purchasing of crypto are possible through a blockchain, a digital ledger that uses complex cryptography to record transactions. This process is intended to be both secure through its irreversible chaining of encrypted transactions, as well as transparent since all recorded transactions are available to the public. [3] In centralized exchanges such as FTX, individuals can make cash or crypto deposits in order to buy and trade other cryptocurrencies. [4] These exchanges generate revenue through deposit or transaction fees, but store customer funds in their own centralized wallet as opposed to each customer having an individual wallet. FTX’s collapse was a result of the mismanagement and theft of these funds and the manipulation of investors, who were unaware of the internal schemes and monetary crises occurring within the company.

On November 11th, 2022, FTX filed for bankruptcy, as $8 billion in customer funds went missing and FTX was unable to meet customer withdrawal requests. This happened because of the backdoor relationship between FTX and its sister company, Alameda Research. In 2017, Samuel Bankman-Fried, along with several of his acquaintances from college, founded Alameda Research, which operated as a crypto hedge fund and trading company. [5] Bankman-Fried initially used Alameda’s profits to fund FTX, which created its own token called FTT, allowing for discounts on exchange fees. [6] FTT was minted by FTX, meaning its value was intrinsically tied to the value of FTX itself. As FTX grew rapidly, prominent investors put new capital into the company. Behind the scenes, however, Bankman-Fried was using FTX customers’ funds to finance Alameda’s business, which was strictly against FTX’s own terms of service. By allowing an exception in FTX’s coding, Alameda could hold a negative account. With this account, Bankman-Fried could withdraw unlimited user funds from FTX to make risky bets that frequently turned into losses. [7] Additionally, Bankman-Fried and his associates used these withdrawal systems for their own agendas, such as investments into less popular—and as such, more unstable—cryptocurrencies, as well as exchanges, hedge funds, illegal political donations, and personal expenditures such as real estate. [8] In Spring 2022, Bankman-Fried diverted even more customer funds to pay off several loans due to the collapse of several cryptocurrencies, causing a minor crisis in the overall crypto market. [9]

This blatant theft of customer funds would be exposed on November 2nd, 2022, with the publication of a CoinDesk article [10] which showed that approximately half of Alameda’s assets on its balance sheet consisted of FTT tokens—meaning that Alameda largely depended on an illiquid currency that Bankman-Fried himself created. [11] Once this information became public, business rival and fellow exchange Binance liquidated their FTT tokens to create a withdrawal run, resulting in mass withdrawal requests from customers and the tanking of FTT’s price. [12] Due to Alameda having lost $8 billion worth of customer funds, as well as the inability of Alameda’s FTT to cover its losses as collateral, FTX was unable to accommodate withdrawal requests. [13] Ultimately, it was the theft of customer funds that caused FTX—and subsequently Alameda—to file for bankruptcy on November 11th, the same day that Bankman-Fried stepped down as its CEO. [14] On December 12th, because of the aforementioned schemes, Bankman-Fried was arrested by Bahamian officials and extradited to the United States. [15]

The first legal consequence of this debacle will likely come in the form of Sam Bankman-Fried’s trial, as well as the deliberation on how the lost funds will be recovered. Currently, Bankman-Fried is under house arrest at his parents' home, after posting a $250 million bail bond. [16] His arrest and extradition from his home in the Bahamas were followed by a criminal indictment in which the United States charged him with wire fraud, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, commodity fraud, securities fraud, conspiracy to commit money laundering, and defrauding the United States and its election laws. [17] Bankman-Fried pled not guilty to all charges. [18] If convicted of all these charges, Bankman-Fried could potentially face up to 115 years in prison. In addition to the criminal charges, he also faces civil suits from both the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. [19] However, as of February 13th, 2023, these cases have been put on hold until the conclusion of the criminal trial. The U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, Damian Williams, cited in his February 7th appeal, “All the facts at issue in the civil cases are also at issue in the criminal case.” [20] At the time of publication, the criminal trial is scheduled for October 2nd, 2023.

In the short time between the indictment and the time of publication, there have been several complications and interesting turns in the proceedings of the criminal case. On January 27th, the Department of Justice requested District Court Judge Lewis Kaplan ban Bankman-Fried from communicating with former colleagues or employees of FTX, as he was found to have messaged former FTX general counsel Ryne Miller via Signal—an app that allows encrypted messaging. [21] The prosecutors claimed that Bankman-Fried was attempting to sway witnesses who would potentially aid or incriminate him in October’s trial. Additionally, on February 14th, Kaplan ordered a ban on the use of virtual private networks (VPNs), which could allow someone to have their information disguised when using the internet, as a new condition of Bankman-Fried’s bail. [22] While Bankman-Fried and his attorneys asserted that he was using it to watch NFL playoff games, prosecutors alleged that Bankman-Fried may have been using a VPN to help transfer assets from Alameda. The Department of Justice (DOJ) is currently suggesting that Bankman-Fried be banned from accessing the internet and utilizing any devices that can connect to the internet, except in special circumstances. [23]

Despite the overwhelming evidence presented against Bankman-Fried, it is still unclear whether he will be found guilty of some or all of these charges due to the current stage of the case. However, these post-bail actions taken by Bankman-Fried will not only tighten his bail conditions, but also likely will not do him or his defendants any favors when the trial commences. Additionally, some of Bankman Fried’s notable colleagues, including Alameda CEO Caroline Ellison and FTX cofounder Gary Wang, have pleaded guilty to their own charges and are reportedly working with prosecutors to potentially testify against Bankman-Fried. [24] The individuals formerly in control of FTX will have their lives burdened by this trial, although many more lives were ruined by their actions.

The ongoing bankruptcy case of FTX is extremely important to the creditors as well as customers who lost significant amounts of money from the fraudulent exchange. FTX filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the state of Delaware. [25] According to a presentation by FTX’s legal counsel, including Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, the debtors have identified around $5.5 billion in assets. [26] These assets include fiat money and crypto located in brokerage accounts, venture investments, and Bahamian property. These expenditures are all being traced in order to recover as much capital as possible. [27] For example, on February 15th, reports circulated about negotiations to recover a $400 million investment made into a Brazilian hedge fund called Modulo. [28] Additionally, politicians who received donations from Bankman-Fried have been contacted about returning some of the donated capital. [29] Presuming all of the identified $5.5 billion worth of assets are recovered, it would only be a portion of the $8 billion in reported liabilities. [30] Moreover, given the early stage of the bankruptcy process, it will be some time before those who lost money can potentially see its return. The next important step will take place on March 8th, when a scheduled omnibus hearing will gather further general information and evidence for this case. [31]

The final implication of FTX’s collapse will be the future of regulatory measures on the entire crypto market. The collapse of a crypto exchange giant the size of FTX has sent shockwaves through the country, with many congresspeople beginning to call for more complex and stricter regulation of the industry. The issue is so urgent that the Republican Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, Patrick McHenry, is cited as being “very eager to engage” with Democrats on addressing the issue of regulation. [32] While some legislation has gained traction in recent months, including legislation promoting the oversight of stablecoins—which are cryptos tied to the United States dollar—nothing substantial or impactful has yet to pass. [33] In fact, the only “regulations” currently in place at the federal level are those given by different financial administrations, such as the aforementioned Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and Securities Exchange Commission (SEC). The pair have cracked down on several crypto exchanges, yet these agencies disagree on what crypto is. The SEC views crypto as a security, such as a stock or bond, and it has taken an aggressive approach to monitor exchanges; meanwhile, the CFTC identifies crypto as a commodity—as in a raw material worth value, such as livestock in the case of agriculture—which is not a security. [34] The federal government has not provided a concrete answer of whether crypto falls under the jurisdiction of either of these administrations, with the US Congressional Research Service stating,

“Currently, there is no comprehensive regulatory framework for cryptocurrencies or other digital assets. Instead, various state and federal financial industry regulators apply existing frameworks and regulations where exchanges or digital assets resemble traditional financial products. As such, regulators may treat digital assets as securities, commodities, or currencies depending on the circumstances.” [35]

A bill titled the “Digital Commodities Consumer Protection Act” was primed to give the CFTC jurisdiction over crypto, but it has fallen out of favor given FTX’s collapse. [36] While this debate continues without a clear resolution, there is confidence that FTX’s collapse will drive lawmakers to have more urgency in passing legislation.

The collapse of FTX has undoubtedly left a sizable mark, not only on the crypto industry but also on the legal environment surrounding it. While Bankman-Fried’s actions have not yet been determined to have malicious intent or the result of poor organizational structure, the consequences of his actions have changed the lives of many people across the globe. When Bankman-Fried’s trial concludes, the bankruptcy case will re-appropriate as many lost assets as it can, and hopefully, the U.S. will pass legislation for a more organized approach to regulating the crypto industry. Ultimately, the crypto landscape in America will be unequivocally changed by these distinctive events.

Sources

Patel, Dee. n.d. “A Beginner’s Guide to Cryptocurrency.” Penn Today. Accessed February 12, 2023.

Ibid.

SoFi’s Crypto Guide For Beginners. Social Finance. 2023.

Ibid.

Goswami, Rohan, and Mackenzie Sigalos. “How Sam Bankman-Fried Swindled $8 Billion in Customer Money, According to Federal Prosecutors.” CNBC. December 18, 2022.

Ibid.

Goldstein, Matthew, Alexandra Stevenson, Maureen Farrell, and David Yaffe-Bellany. “How FTX’s Sister Firm Brought the Crypto Exchange down.” The New York Times, November 18, 2022.

Goswami, Rohan, and Mackenzie Sigalos. “How Sam Bankman-Fried Swindled $8 Billion in Customer Money, According to Federal Prosecutors.” CNBC. December 18, 2022.

Ibid.

Allison, Ian. “Divisions in Sam Bankman-Fried’s Crypto Empire Blur on His Trading Titan Alameda’s Balance Sheet.” CoinDesk. November 2, 2022.

Goswami, Rohan, and Mackenzie Sigalos. “How Sam Bankman-Fried Swindled $8 Billion in Customer Money, According to Federal Prosecutors.” CNBC. December 18, 2022.

Goldstein, Matthew, Alexandra Stevenson, Maureen Farrell, and David Yaffe-Bellany. “How FTX’s Sister Firm Brought the Crypto Exchange down.” The New York Times, November 18, 2022.

Goswami, Rohan, and Mackenzie Sigalos. “How Sam Bankman-Fried Swindled $8 Billion in Customer Money, According to Federal Prosecutors.” CNBC. December 18, 2022.

Ibid.

Yaffe-Bellany, David, William K. Rashbaum, and Matthew Goldstein. 2022. “FTX’s Sam Bankman-Fried Is Arrested in the Bahamas.” The New York Times, December 12, 2022.

Helmore, Edward. “Sam Bankman-Fried Pleads Not Guilty in FTX Case.” The Guardian, January 3, 2023.

“United States v. Samuel Bankman-Fried, a/k/a ‘SBF,’ 22 Cr. 673 (LAK).” Justice.gov. January 6, 2023.

Ibid.

Helmore, Edward. “Sam Bankman-Fried Pleads Not Guilty in FTX Case.” The Guardian, January 3, 2023.

Wright, Turner. “US Attorney Requests SEC and CFTC Civil Cases against SBF Wait until after Criminal Trial.” Cointelegraph. February 7, 2023.

Lyons, Ciaran. “US Prosecutors Seek to Ban SBF from Signal after Alleged Witness Contact.” Cointelegraph. January 28, 2023.

Kaplan, Lewis A., Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and The, Silvio J. 2023. “Case 1:22-Cr-00673-LAK

Document 50 Filed 01/27/23.” Courtlistener.com. 2023.

Ibid.

Goldstein, Matthew, and David Yaffe-Bellany. “FTX Inquiry Expands as Prosecutors Reach out to Former Executives.” The New York Times, February 4, 2023.

“Chapter 11 - Bankruptcy Basics.” n.d. United States Courts. Accessed February 19, 2023.

“FTX Trading Ltd. Case No. 22-11068.” n.d. Kroll Restructuring Administration. Accessed February 19, 2023.

Ibid.

Chang, Ellen. “FTX Collapse: Creditors Could See Return of Huge Hedge Fund Investment.” Thestreet.com. February 18, 2023.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“FTX Trading Ltd. Case No. 22-11068.” n.d. Kroll Restructuring Administration. Accessed February 19, 2023.

Hamilton, Jesse. “After FTX: How Congress Is Gearing up to Regulate Crypto.”

CoinDesk. January 23, 2023.

Ibid.

“How Are Cryptocurrencies Regulated in the U.S. and the EU?” Dow Jones Professional. Dow Jones. August 28, 2020.

Zelkowitz, Jeff. “2023 CMC Crypto Playbook: US Crypto Regulation Outlook by APCO.” CoinMarketCap. January, 2023.

Ibid.

Yeezy & Adidas: The Intersection of Intellectual Property, Licensing, and Contracts

Louboutin’s red bottoms, the Coca Cola recipe, Tiffany blue – these are all examples of intellectual property. Intellectual property (IP) refers to works that are created by an individual or group’s original ideas – their intellect. Intellectual property law governs the author’s ability to exercise special rights over these works. Despite many peoples’ lack of knowledge or notice of it, intellectual property has infiltrated almost every aspect of human life. Every time one sees an advertisement, buys or consumes a product, reads a book, listens to a song, or watches a movie, they are actively interacting with a form of intellectual property. Celebrities and public figures in particular are, in many ways, dependent on the benefits that intellectual property rights can generate. Following his extremely controversial public statements, rapper-turned-businessman Kanye West admitted to losing $2 billion worth of brand deals and business relationships in one day due to public outrage. Most notably, Adidas – the manufacturer and distributor of West’s “Yeezy” products – has publicly severed ties with him and is attempting…

November 2022 | Tia Zghaib (Staff Writer and Editor)

Louboutin’s red bottoms, the Coca Cola recipe, Tiffany blue – these are all examples of intellectual property. Intellectual property (IP) refers to works that are created by an individual or group’s original ideas – their intellect. Intellectual property law governs the author’s ability to exercise special rights over these works. Despite many peoples’ lack of knowledge or notice of it, intellectual property has infiltrated almost every aspect of human life. Every time one sees an advertisement, buys or consumes a product, reads a book, listens to a song, or watches a movie, they are actively interacting with a form of intellectual property.

Celebrities and public figures in particular are, in many ways, dependent on the benefits that intellectual property rights can generate. Following his extremely controversial public statements, rapper-turned-businessman Kanye West admitted to losing $2 billion worth of brand deals and business relationships in one day due to public outrage. [1] Most notably, Adidas – the manufacturer and distributor of West’s “Yeezy” products – has publicly severed ties with him and is attempting to lay claim to a large portion of the intellectual property associated with the brand. Adidas stated that it is “the sole owner of all design rights to existing products as well as previous and new colorways under the partnership.” [2] Thus, examining this dispute and its consequences provides for an effective framework to analyze the inner workings of IP as a whole.

The three main categories of IP are copyright, trademark, and patent. Copyright protects an author’s ability to distribute and replicate their work; this includes songs, books, and films. In contrast, trademarks do not focus on replication and instead are marks that identify a particular product or company and distinguish it from others. [3] This includes logos, business names, jingles, colors, and slogans. The name and logo of West’s brand “Yeezy” are the registered trademarks of his company, Mascotte Holdings, Inc. [4] Thus, through his company, West has exclusive and sole ownership of the Yeezy trademarks and brand. Similarly, Adidas has its own registered trademarks for its name, logo, and other identifiers. The two brands’ decision to partner up for the Yeezy-Adidas line did not affect the separation of their trademarks or change their ownership.

The third main category of IP is patent. Title 35 of the U.S. Code governs patents and requires that they be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). [5] Patents allow the creator of a unique invention to exercise sole and exclusive rights to produce, distribute, and profit from their invention. Utility and design patents are two types of patents. While utility patents protect the way an invention functions or how it is used, such as digital software and medical patents, design patents protect the appearance or design of a product—like the physical layout of an iPhone. [6] Design patents are often used in the fashion industry, particularly for sneakers. Thus, it is no surprise how important design patents are to the Yeezy-Adidas partnership. A close investigation of the USPTO design patents registrations for Yeezy shoes reveals that Adidas is the owner of every Yeezy design except for one: the Yeezy slides. [7] Therefore, the Yeezy-Adidas partnership is not clear cut regarding the ownership of the different IP associated with the fashion line.

Considering the amount of IP involved in the Yeezy-Adidas line, it becomes obvious that the parties entered into a licensing agreement. Intellectual property licensing involves an owner of IP allowing another entity to use its IP in exchange for a fee, called a “royalty.” [8] Although the licensing agreement for the Yeezy-Adidas partnership is private, it is reasonable to make some conclusions regarding its nature. The agreement most likely provided for Adidas designing, manufacturing, and distributing the Yeezy products, which is why Adidas is the registered owner of these design patents under the USPTO. However, the licensing agreement allowed Adidas to distribute these products under the Yeezy name—West’s trademark—in exchange for a 15% royalty on the wholesale price per product. [9] Thus, both Adidas and Yeezy were able to profit from each others’ IP, with Yeezy using Adidas’ designs and Adidas using the Yeezy name. However, this formerly harmonious partnership now faces a potentially messy legal battle due to the recent split.

Beginning with its statement severing ties and claiming that it is the “sole owner” of Yeezy designs, Adidas has made it clear that it intends to continue to own and profit from these designs. However, West has disputed these claims by alleging that Adidas stole his designs. [10] So, what does this mean for Yeezy? The private nature of the licensing contract limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding possible legal battles that may stem from the dispute. If Adidas did not have the legal grounds to terminate the contract prior to its expiration, then West may be able to sue for breach of contract and other related claims. Moreover, if the contract provided that the designs be registered under Yeezy and Adidas violated this provision, West could be entitled to damages and possibly invalidate the company’s rights to the patents. However, it is highly unlikely that Adidas breached the contract in this way and exposed itself to these legal claims.

Assuming that Adidas is indeed the rightful owner and designer of the patents, it could technically continue to distribute the Yeezy products. However, Adidas no longer has the right to use the Yeezy brand name since they terminated their contract with West, who was allowing the company to use his trademarks. Theoretically, Adidas could continue selling Yeezy products exactly how they are designed, provided that they remove any Yeezy logos and sell them under a different brand. In fact, Adidas CFO Harm Ohlmeyer confirmed the company’s intentions to sell the designs associated with Yeezy under a different trademark. Ohlmeyer summarized the implications of the Yeezy-Adidas IP split when he stated, “We own all the IP, we own all the designs… It's our product. We do not own the Yeezy name.” [11] He also stated that Adidas would be saving money because they no longer have to pay West the royalties for the use of his trademark. As for Yeezy, the brand could continue to operate, but it would have to come up with entirely new designs for all products that were associated with the Adidas partnership, since Adidas owns all the design patents except the slides. Therefore, both companies would be losing some of the benefits they gained from their partnership, but at least they would be able to walk away maintaining some of their intellectual property.

Examining the Yeezy-Adidas split sheds light on the complexity of IP law and how it intersects with other areas of law. The IP associated with one brand can range from clear-cut ownership to a very messy relationship. Different owners of different categories of IP can split and cause more confusion about who owns what. Moreover, the licensing agreements and contracts that dictate ownership of the IP can both help and hinder this confusion. As such, it is more important than ever for both attorneys and the public to expand their knowledge of the complex yet essential area of law that governs intellectual property.

Sources

Hipes, Patrick, “Kanye West Says He Lost $2 Billion In One Day Amid Controversy, Calls Out

Ari Emanuel.” (Deadline: October 2022).

Sarlin, Jon, “Yeezy Without The Ye? Who Is New ‘Sole’ Owner?” (CNN: October 2022).

“Trademark, Patent, or Copyright.” (USPTO).

Isaiah Poritz, Chris Dolmetsch, and Bloomberg, “Adidas Might Be Cutting Ties to Kanye west, but The Company Could Still Be Paying Him Millions of Royalties Into 2023.” (Fortune: October 2022).

“U.S. Code: Title 35.” (Legal Information Institute).

“1502.01 Distinction Between Design and Utility Patents [R-07.2015].” (USPTO).

Vlahos, Nicholas, “What We Know About Kanye’s Contract With Adidas.” (Sole Retriever:

September 2022).

Isaiah Poritz, Chris Dolmetsch, and Bloomberg, “Adidas Might Be Cutting Ties to Kanye west, but The Company Could Still Be Paying Him Millions of Royalties Into 2023.” (Fortune: October 2022).

Ibid.

Ciment, Shoshy, “Does Kanye West Have a Legal Claim Against Adidas?” (Footwear News:

September 2022).

Fox 13 News Staff, “Adidas owns rights to Yeezy designs, CFO says; will sell products with different name after Kanye West fallout.” (Fox 13 News: November 2022).

Hiding in the Shadows: The Truth Behind the Supreme Court’s Shadow Docket

One of the Supreme Court’s more bizarre cases occurred in 1970, when two lawyers hiked six miles into the woods to request that Justice William O. Douglas prevent Portland, Oregon police officers from using violent tactics to stop protests. In the woods, Justice Douglas held an impromptu oral argument and then left his decision on a tree stump: application denied. This case illustrates how the Supreme Court has relied on emergency applications and summary decisions to produce rulings in time-sensitive situations. Since 2017, however, there has been a significant increase in the number of cases decided through this emergency docket – generating speculation on whether or not its implementation is appropriate. The “shadow docket” was a term coined by University of Chicago law professor William Baude, as he explained that “outside of the merits cases, the Court issued a number of noteworthy rulings which merit more scrutiny than they have gotten. In important cases, it granted stays and injunctions that were both debatable and mysterious. The Court has not explained their legal basis and it is not even clear to what extent individual Justices agree with those decisions…

November 2022 | Kira Kramer (Staff Writer and Editor)

One of the Supreme Court’s more bizarre cases occurred in 1970, when two lawyers hiked six miles into the woods to request that Justice William O. Douglas prevent Portland, Oregon police officers from using violent tactics to stop protests. In the woods, Justice Douglas held an impromptu oral argument and then left his decision on a tree stump: application denied. [1] This case illustrates how the Supreme Court has relied on emergency applications and summary decisions to produce rulings in time-sensitive situations. Since 2017, however, there has been a significant increase in the number of cases decided through this emergency docket – generating speculation on whether or not its implementation is appropriate. The “shadow docket” was a term coined by University of Chicago law professor William Baude, as he explained that “outside of the merits cases, the Court issued a number of noteworthy rulings which merit more scrutiny than they have gotten. In important cases, it granted stays and injunctions that were both debatable and mysterious. The Court has not explained their legal basis and it is not even clear to what extent individual Justices agree with those decisions…As the orders list comes to new prominence, understanding the Court requires us to understand its non-merits work – its shadow docket”. [2]

Within the shadow docket, emergency applications call for a different procedure than the Court's regular docket. Emergency applications are requests for temporary relief, usually used when a party is seeking a temporary stay of a lower court order. A stay of a lower court order stops the legal proceedings or the action of a party. [3] These applications produce two outcomes: either the Supreme Court denies a petition for certiorari, which is a formal request for the Supreme Court to hear the case, or the Supreme Court accepts the petition and decides the case on its merits. [4] The most important takeaway between the shadow docket and the regular docket is how the application is processed. Emergency stay applications are filed and decided faster than petitions in the regular docket. A regular decision on the merits takes months from the filing of the petition, whereas an emergency stay application can receive a decision within days or hours—including after business hours. [5] Furthermore, emergency applications do not come with a written opinion or an explanation for the decision, which fosters a lack of transparency.

A regular docket must be filed within 90 days of the lower court judgment. [6] The petition is usually accepted around six weeks after its filing. Then, it takes two months to be argued after the case was accepted. The case is ultimately decided one to several months after it was argued. Regular decisions using the merit docket usually have oral arguments lasting hours. Following the oral argument, a lengthy ruling is produced including opinions from both the majority and minority. The majority opinion is a decision that is joined by more than half of the judges in the Supreme Court. On the contrary, shadow docket cases do not require any oral argument, will have a decision rendered in days or even hours, and usually receive little to no explanation for that decision. Clearly, there is a significant discrepancy between the two dockets and the effect that the different procedural standards have on the laws impacted by their decisions.

There are current criteria that a case must meet in order to be considered for an emergency application. The first is that there must be a reasonable probability—a factual basis that would lead a reasonable mind to a conclusion—that four justices will grant certiorari and agree to the merits of the case. [7] Next, there must be a fair prospect—a 51% chance that a person will be successful in their pursuit of legal proceedings—that a majority of the Court will conclude upon review that the decision below on the merits was erroneous. [8] Then, after exploring the relative harms to the applicant, respondent, and the interests of the public at large, the Court must determine that irreparable harm will result from the denial of the stay. [9] Essentially, a party requests relief from a lower court order that is about to be implemented, arguing to the Supreme Court that the lower court decided incorrectly. If the party’s petition meets the aforementioned criteria and can prove that they will face irreparable harm, then the emergency application will be added to the Court’s shadow docket.

There are two plausible tracks that the temporary relief provided by the shadow docket provides for Court decisions. [10] The decisions made by the docket only last until the Court denies the petition for certiorari, meaning the lower court's ruling stands, or the Court eventually decides the case on the merits—which will produce a final ruling. [11] However, the shadow docket ruling impacts policy beyond these two tracks. For example, any election-related issues that are time-sensitive and decided using the shadow docket take precedence over the lower court ruling because the Court will not hear the merits case before the election occurs—giving the emergency application the final say. Additionally, COVID-related rulings are an example of how shadow docket rulings become precedent across the U.S. in times of emergency and beyond.

Historically, shadow docket cases have been more controversial and obscure, leading to public disagreement and further transformation of the docket over time. At first, an individual Justice would be issued the case, and then they produced a decision without the involvement of the other Justices. The treatment of the shadow docket started in the 1980s, when the Court ceased to adjourn during summers. Justices then began to decide on shadow docket cases in unison. [12] Another historical case, coincidentally involving William O. Douglas, was the use of emergency applications to grant a stay of the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenburg—who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The shadow docket was also used to issue an emergency injunction ordering a halt on the Nixon administration’s bombing of Cambodia. [13] Additionally, the shadow docket has been used as a way for the Court to manage its workload by quickly issuing decisions to refuse to take on various cases. Whether to manage the caseload or respond to emergency situations, there has always been anonymity surrounding the use of the shadow docket.